“A Dirty Word for Bitter Girls”: An Ode to Blog Era Feminism

Make it stand out

If TikTok’s algorithm has identified you as having demographic information that aligns you to feminist content, your swiping experience may look like this: Open app. Watch a 20-second video of a young woman expressing discomfort with cosmetic surgery trends. Read comments like: “Let women enjoy things”; “Why do we criticize women for their choices but not men? Feels like internalized misogyny to me”; ”I got surgery because I wanted to, and I got my boyfriend to pay for it - sprinkle sprinkle!”

It is not just feminists experiencing this. Creators on social media platforms have expressed frustration with a perceived lack of critical thinking when it comes to online discourse. Impacts from a global pandemic and defunded education aside, it's no surprise that we’ve reached this point. On TikTok, 7-second videos still garner the most engagement. Across all platforms, hot topics quickly run stale due to the sheer amount of content. Many swipers are disinterested in analytical discussions at all.

One’s online identity is intertwined with their consumer identity: You are online to consume, and creators exist to help you make your choices. Now choice feminists, trad wife TikTokers, and Soft Life influencers saturate the space, leaving little room for young women to examine trends critically without being accused of a cardinal internet sin: being a hater.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

I did not identify as a feminist until 2012, I was about 13 and my growing appetite for feminism collided with having to navigate new restrictions after my family relocated to Saudi Arabia. In parallel, I discovered punk subcultures. The riot grrrl scene and its figureheads became mini goddesses to me. One day while researching Kathleen Hanna, I came across the FBomb. Created in 2009, FBomb was led by 16-year old Julie Zeilinger with a mission to shed light on the teenage perspective in contemporary feminist discussions. The stylised bomb was fitting - Julie and other contributors wrote with such fervour it was as if they wanted to tear down the walls that tried to make young women feel small. Essays covered a range of topics including representations in media, ideological differences within feminism, dating as a feminist, and impacts of consumerism on body image. It was my daily newspaper.

The FBomb became a gateway to a world of bloggers engaging an audience hungry for feminism. I was soon introduced to Feministing, run by sisters Jessica (writer of The Purity Myth) and Vanessa Valenti. Racialicious provided much needed intersectional discussion.

“One’s online identity is intertwined with their consumer identity: You are online to consume, and creators exist to help you make your choices.”

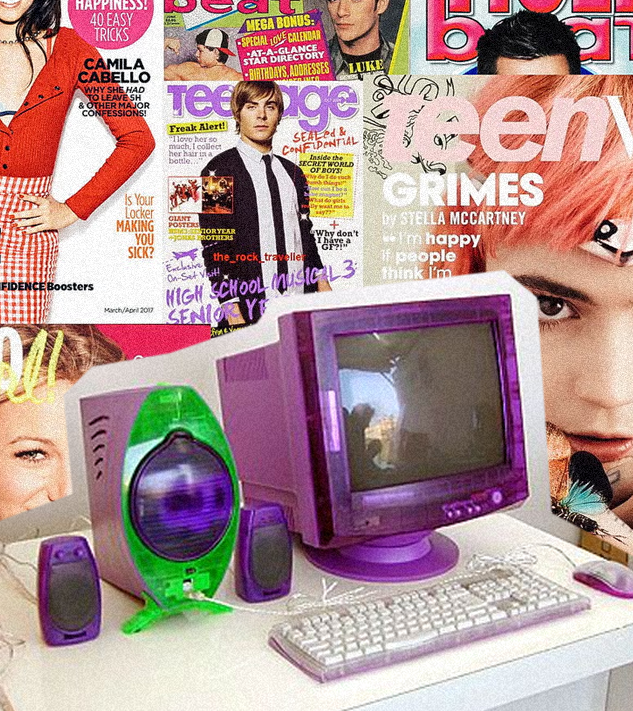

Many writers documented their own personal explorations - much like daily vlogs, without the pressure of being camera ready. One example of this was a blog called The Seventeen Magazine Project. A high school senior, Jamie Keiles, challenged herself to take ‘advice’ from Seventeen Magazine for 30 days and documented it with a critical eye.

In one of Jamie's early posts, she wittily described painting her nails lavender, a colour that reminded a Seventeen reader of “all things sophisticated and girly”:

“Something that is beyond me is the notion of conflating sophistication with girlhood. Something that is further beyond me is the association of colours with age and gender. Despite this fact, I now have lavender nails (and I quite like them.)”

Fresh off of Fashion Rookie fame, Tavi Gevinson started Rookie in 2010. Teens were writing personal essays, creating art, reviewing movies, and dissecting fashion trends. Meanwhile Jezebel was home to edgier, feminist cultural criticism and tapped into a holistic cultural-political movement. Jezebel championed print media (I loved Bust), music, movies, and brands in alignment with the feminist ethos. It was normal to read a review of a piece of media involving a woman that concluded that while it may be enjoyable, it doesn’t make it feminist. They demanded our standards be higher.

What I loved about these websites was that we were treated like a peer audience, not fans. The Do-It-Yourself ethos mirrored the possibilities for those wanting to share ideas. A lot of us were still coding our own MySpace and Tumblr pages. It felt cool to be a feminist at a time when it was treated like a dirty word for bitter girls that wanted to rain on everyone’s parade.

Of course, it was not all perfect: many of the popular voices had to answer for their lack of intersectionality. Trans-inclusionary rhetoric was not the norm, and some struggled to criticise pornography (where categories like Revenge Porn were growing) without falling into anti-sex worker pitfalls. In indie or punk spaces, Black women were still footnotes and subcategories.

One could argue that the need to make feminism popular was part of the problem. For some, the chief concern was making feminism more palatable. Any celebrity saying “I’m a Feminist'' was seen as a win. These bloggers could not have predicted the social media of today, but in hindsight, perhaps it was shortsighted to not prioritise critical thinking.

Words: Camille Duke