Angst is For the Girls: Exploring How Existentialism Shapes the Adolescence of Women

Make it stand out

Existentialism and the questioning of self are at the centre of many coming-of-age tales: Who are you? And why do you like what you like? Unfortunately, this line of questioning does not cease, even when you become a bonafide adult, but in your formative years these questions seem louder and more pressing as you aim to rationalise internal and external changes with an underdeveloped prefrontal cortex, confusing boundaries between childhood and adulthood, and an influx of hormones messing with you. Naturally, angst is a byproduct of such growing pains, and nobody understands angst more than teenage girls. In the wise words of Cecilia Lisbon: “Obviously, Doctor, you've never been a 13-year-old girl.”

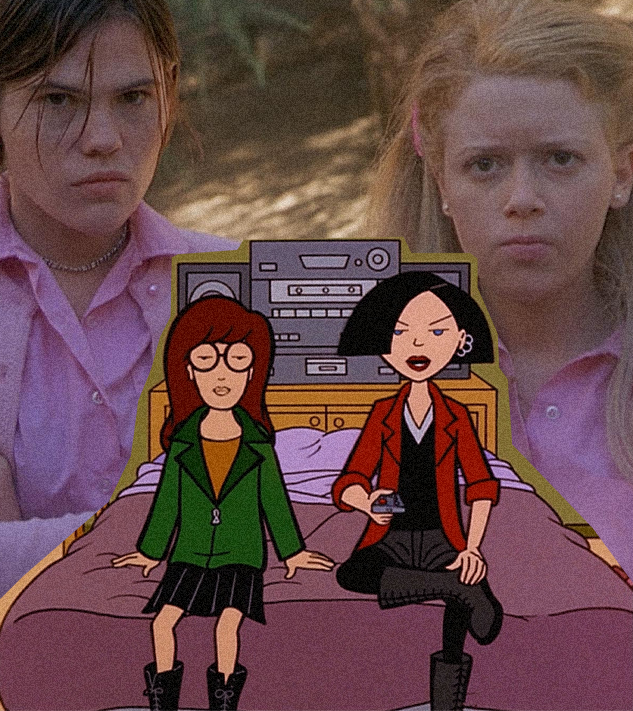

Television and film have illustrated, albeit clumsily at times, the akin relationship between girlhood and existential dread through the beloved ‘angsty girl’ archetype: A young female character, often in her teens with a certain level of indifference, frustration and distaste for the world. Just one episode of Daria paints this character in intense detail. Despite the frequent cheesy lines about defiance and the not-like-other girls-isms, Daria resonates amongst many of us who identify with girlhood for a more imposing reason than most. There is a gender dimension to angst and coming-of-age that this archetype embraces wholeheartedly.

Under the wider umbrella of coming-of-age, it is assumed that girlhood and boyhood are linear. Same but different. Parallel and corresponding lived identities that prompt the same feeling of adolescent levity. But being a girl is riddled with a nuance that is specific to the gender, film and TV professor Mary Celeste Kearney in Coalescing: The Development of Girls’ Studies remarks, “...There are many ways to be a girl, and these forms depend on not only the material bodies performing girlhood but also the specific social and historical contexts in which those bodies are located.”

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Existentialism and angst permeates: The historical subordination of girls and women is resonant in the terrain of girlhood and womanhood. Scholars Jacqueline Warwick and Allison Adrian soberingly observe that “a boy becomes a man (and more rapidly than) a girl becoming a woman precisely because he is differently positioned to have greater agency and earlier access to power”. Early on in our lives, women come to have a level of recognition and awareness of this power imbalance. Angst is then an unsurprising response to this level of inequity which in turn cultivates a desire for agency and independence.

“Early on in our lives, women come to have a level of recognition and awareness of this power imbalance. Angst is then an unsurprising response to this level of inequity which in turn cultivates a desire for agency and independence.”

10 Things I Hate About You (1999), a classic teen film features two sisters, Kat and Bianca. Their father sets a rule that Bianca cannot date until Kat does. Upon informing her classmate Cameron (who in fact has a crush on Bianca) about this rule, Cameron pays Patrick, the bad boy with a secret heart of gold at their high school, to woo her sister. Kat is the epitome of the 90s angsty teen girl archetype, painted as the socially aware, unpalatable, man-hating untamable ‘shrew’. Contrastingly, Bianca is a girly girl who craves the normalcy of typical teenagehood that she feels has been denied to her due to her father’s rules. Kat’s eponymous poem listing the 10 things she hates (spoiler: but doesn’t actually hate as she falls for him) about Patrick is a deeply contested point of the movie.

The poem for some signifies Kat’s regression into a subdued obedient girl having been finally worn down (see Elizabeth Deitchaman’s comments), whereas others, such as Associate Professor Rachel McLennan, view it as being far more ambiguous. The film has significant failings, particularly as the primary driving source of the plot is the literal act of wagering on a girl. Also, in one scene, Kat flashes her adult soccer coach to get Patrick out of detention. Yet, I think it still remains an interesting depiction of the angsty girl archetype. Rachel McLennan again, sees the film as an exploration of both Kat and Bianca’s attempt to “negotiate space for themselves within American culture at a time when adolescent girls are both idealised subjects and impossible projects”. Like most popular teen movies at the time, the movie decades later does not necessarily bode well due to the presence of rampant sexism. This is hardly surprising as the film is an adaptation of sexist literature, Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. Kat is a highly flawed character - she’s undoubtedly an “I’m not like other girls” girl - yet she remains for some a beloved contrived portrayal of the remnants of the 90s riot grrrl era, with her distaste for the high school popularity machine and her bold expression of adolescence.

Another classic, But I’m A Cheerleader (1999) is the quintessence of a campy teenage film. It is a poignant illustration of both the gender and sexual dimensions of the female youth experience. The queer femme film, whilst deeply satirical and surreal, features intelligent social criticism within the muddy waters of teenagehood and teen angst. Director Jamie Babbit, in an interview with the LA Times in 2000, noted that teenagers were the most important audience for this film because she felt that they are “the most in trouble as far as dealing with their identity”. Megan, the titular cheerleader, embodies the conventional image of a cheerleader, with a love for all things pink and her relationship with a football player. However, she finds it difficult to reconcile this with another part of her identity, her sexuality. By the end of the movie, Megan embraces both aspects of her identity, her lesbianism, and her femininity, which are often portrayed as being antithetical within the film. In contrast to Megan, Jan, another character, is straight and masculine and as a result of her appearance she struggles to be recognised as straight and is heavily dismissed. A considerable amount of teen angst stems from appearance and using appearance as a tool to convey our innermost selves. But I’m A Cheerleader, effectively subverts this whilst also exploring queer identities within the broader context of sexual identity markers, which feels rather contemporary for a 90s movie.

In contrast, male angst is often portrayed as an outward force, like the eye of the storm, forcibly drawing others into their emotional turmoil. Whereas, female angst is frequently portrayed as a less overt internal force, and when displayed, it tends to take the form of a caricature such as Kat in 10 Things I Hate About You and Daria. The angsty male archetype is frequently tormented by their previous transgressions and traumatic past. A key plot device is that their angst is often triggered by the brutal victimisation of a female character in their lives: Like the murder of a former lover or mother or both. In the 90s, comic book author Gail Simone coined the term “women in refrigerators” to describe a trope she noticed in comic books, where many of her favourite female characters met “untimely and often icky ends” to advance the male characters’ stories. There is a generous slew of broody angsty male heroic lead characters with an inflated sense of importance in a range of TV shows and films. Such as Batman in any and every iteration of the character, especially The Batman (2022) where Robert Pattinson plays an emotionally wounded “Emo Batman”.

Buffy the Vampire Slayer is subversive in the way it puts this angsty male heroic lead trope on its head: A blonde teen girl takes on an onslaught of masculine action hero storylines and is as angsty as the best of her male peers. The weight of the world is on her shoulders: Her pain is above all, and her male love interests are the ones being fridged. Buffy’s life is a juggling act as she attempts to save the world and to also be a normal high school student. Despite these challenging responsibilities, arguably she’s just as self-involved and self-indulgent as any other male angsty hero. Then again, angst in its nature can make all of us act similarly self obsessed. Ultimately, the classic 90s to 2000s angsty girl archetype, though at times painfully dated, campy and cringy, continues to resonate amongst many of us as we navigate the intricate path of girlhood and womanhood. Angst and frustration at the powers that be feels like a rite of passage. A predictable, anguished, and honest response to external restrictions and societal constraints.

Words: Anesu Hwenga