Carnival Strippers: Desire in Small-Town America

Words: Empress Mirage

I first heard about the hidden world of carnival strippers in a blog post entitled ‘Horrors of the Japanese Hostess Bar’ by director Anna Biller (who also wrote the phenomenal film The Love Witch), and my interest was immediately piqued. Carnival Strippers is the title of the photographic book published in 1975 by acclaimed photographer Susan Meiselas. The photographs by Meiselas, who travelled with a nomadic band of strippers attached to small-town carnivals in the early 1970s, form a unique archive in the US American history of sex work. These are images which tell us about propriety in rural communities and alternative modes of working from a now long-gone era.

Meiselas did extensive interviews with the people who made up the sexual side of these carnivals: the dancers, the carneys, and managers who set up the tents and kept the show running behind the scenes, as well as the clients. By the time she joined the travelling circus in 1972 to document the “...the sometimes hard-to-define line between independence and exploitation…”, the “travelling ‘girl show’ industry” was apparently already dying out.

The carnivals travelled to small towns in New England (Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut), Pennsylvania, and South Carolina – all states where there would have been strict social taboos around sex and eroticism in the public sphere preventing formal strip clubs from being established in the towns where the carnival stopped. Simultaneously, some farm towns in the United States of America would have been so extremely isolated or tiny that having a regular strip club may not have made financial sense.

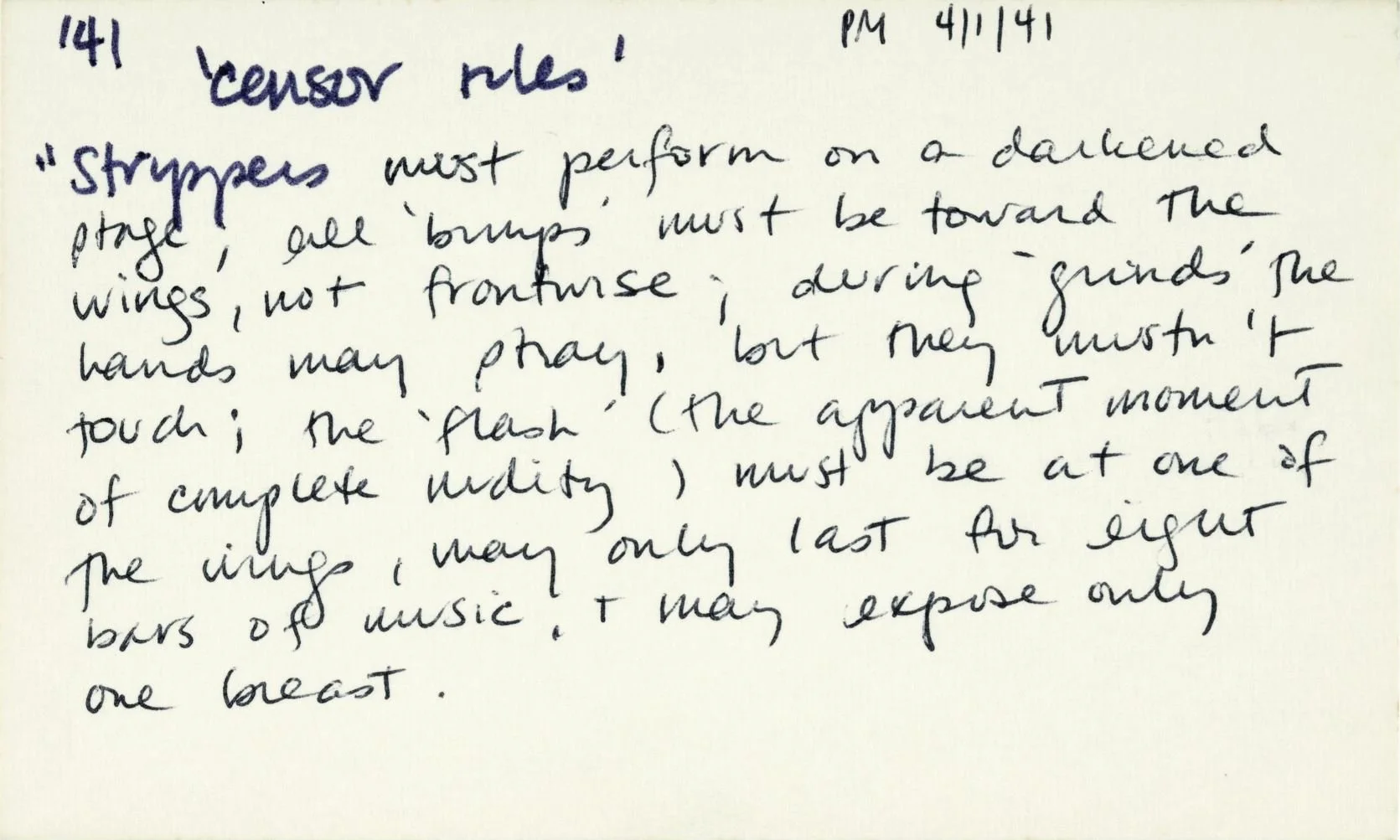

One of my most beloved photos from Meiselas’ chronicle is one of her scribbled notes of the rules given by the “censors” in town, who would likely have been the ‘town fathers,’ (a very antiquated concept of small-town America where the most prominent, wealthy, or established men would have made all the decisions for the community) or formal local municipality. It doesn’t say which town these rules are from, but the meaning is clear: when the strippers came to town, the powers-that-be took the time to meet and decide which sexual acts and level of erotic play would be allowed for the three-to-five days the fair was in town. Even the dance moves were regulated: “...all ‘bumps’ must be toward the wings, not frontwise.” The level of detail given to prescribing how much nudity is allowed is frankly hilarious: …the ‘flash’ (the apparent moment of complete nudity)... may only last for eight bars of music, and may only expose one breast.”

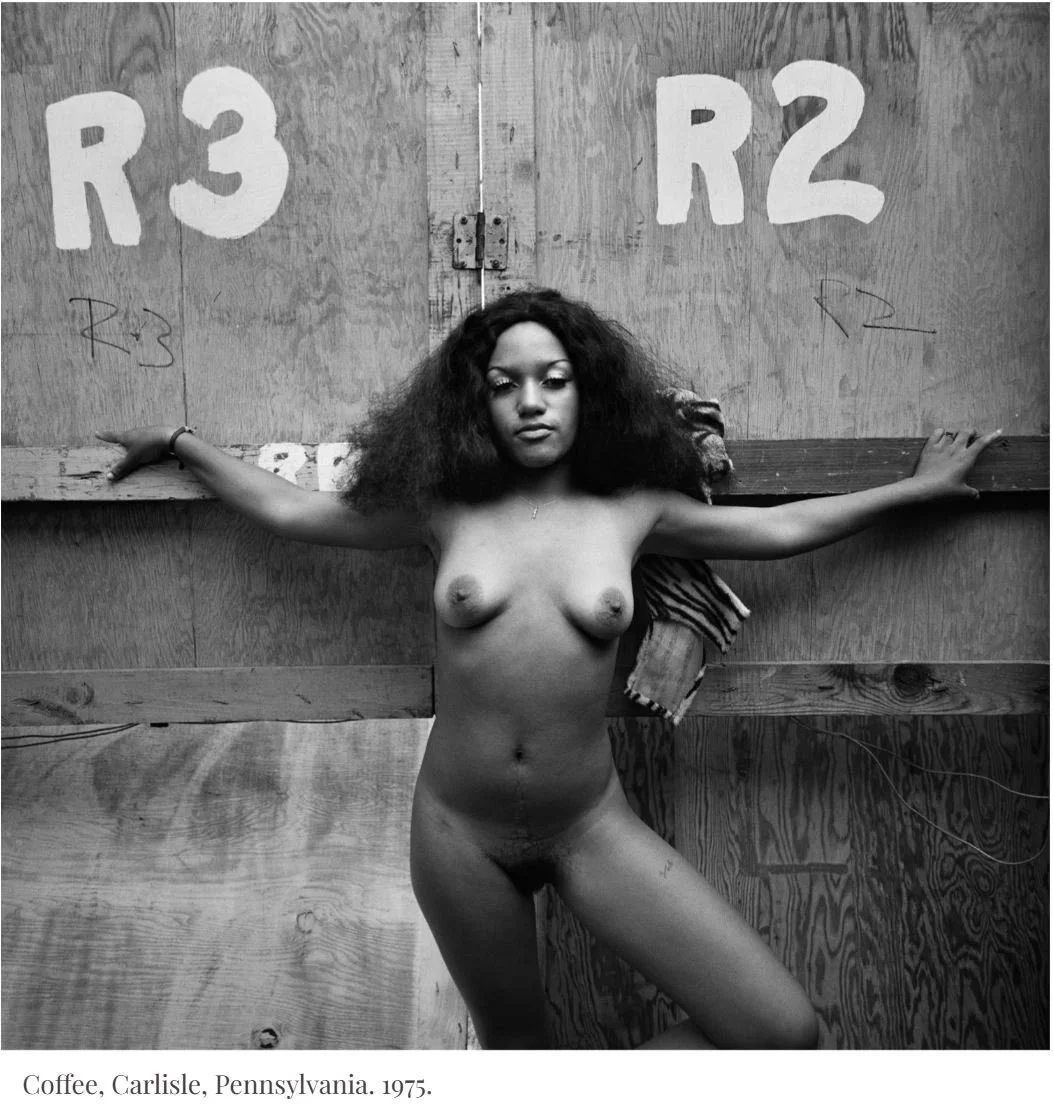

As a Black sex worker and someone who often thinks about what I would have been doing if I were alive in the 1960s and 1970s, because I feel very connected to that era, the world of carnival strippers drew me in because the photographs demonstrate that it was a surprisingly mixed-race working environment (although the clients in the tent always seem to be white men). One dancer in particular, marked only as “New Girl” in the year 1975 caught my eye in particular; the photos of her onstage show her as a complete newbie, with what I assume is a borrowed costume bottom from the carnival over normal black panties, a nude bra top, no shoes, and only her own denim jacket as a kind of covering onstage.

She is photographed behaving as I feel I did when I first began as a sex worker in group settings: gawking at and being impressed by her new coworkers rather than focusing on her stage presence and bringing in her own customers. The black and white portrait of her is intense, and quiet. I wonder if she was a runaway or just from a small town looking for adventure and opportunity, which apparently many of the dancers were. I wonder what her background was, the places she got to see across the Eastern part of the country, and what happened to her once the world of carnival strippers died.

Given the way that Black sexual bodies, Black pleasure, and Black sexuality were and are still very much taboo and transgressive in white America (think of how many times in a movie you have ever seen a close-up shot of two Black people kissing and compare that to how many times you’ve seen white actors do the same thing), seeing that Black sexualities were present on these small-town carnival tours was very exciting for me.

I do think I would have been a carnival stripper! While much of the press on Carnival Strippers, including another blog post by Anna Biller entitled ‘Strippers, Narcissists, and Clowns,’ and this retrospective article by Magnum Photos, focusses on the impact of the male gaze and client consumption on the reality of lived independence of the dancers, they neglect to make note of the fact that queer desires and shows were also a part of these carnivals, as evidenced by the photo entitled ‘Gay New Orleans Bally Call’, of Black gay, queer, trans, and gender-non conforming dancers onstage in Massachusetts. The opportunities arising from working as an erotic carnival worker to Black sex workers

appear to me as a mode of escape from the, “...tactics of masking, secrecy, and disavowal of sexuality that allow Black women to shield themselves from exploitation…” which “...produces a cloak of silence around Black women’s sexual life,” and confronts what Dr. Mireille Miller-Young describes accurately as a kind of censorship within the Black community on anyone who identifies with “non-normative” (non cis-paired heterosexual, Christian, “respectable”) sexuality. Certainly, this kind of censorship threatened to throttle me in my own life as Black woman in the United States to the point that if running away to join the circus had been an option in my youth, I certainly would have considered it.

At the very least, the Magnum Photos article notes that client perspectives, which were from adult men (the apparent rule for entry by the announcer was “No ladies and no babies!”), were as diverse then from the audience as they are now from my own experience as a stripper.

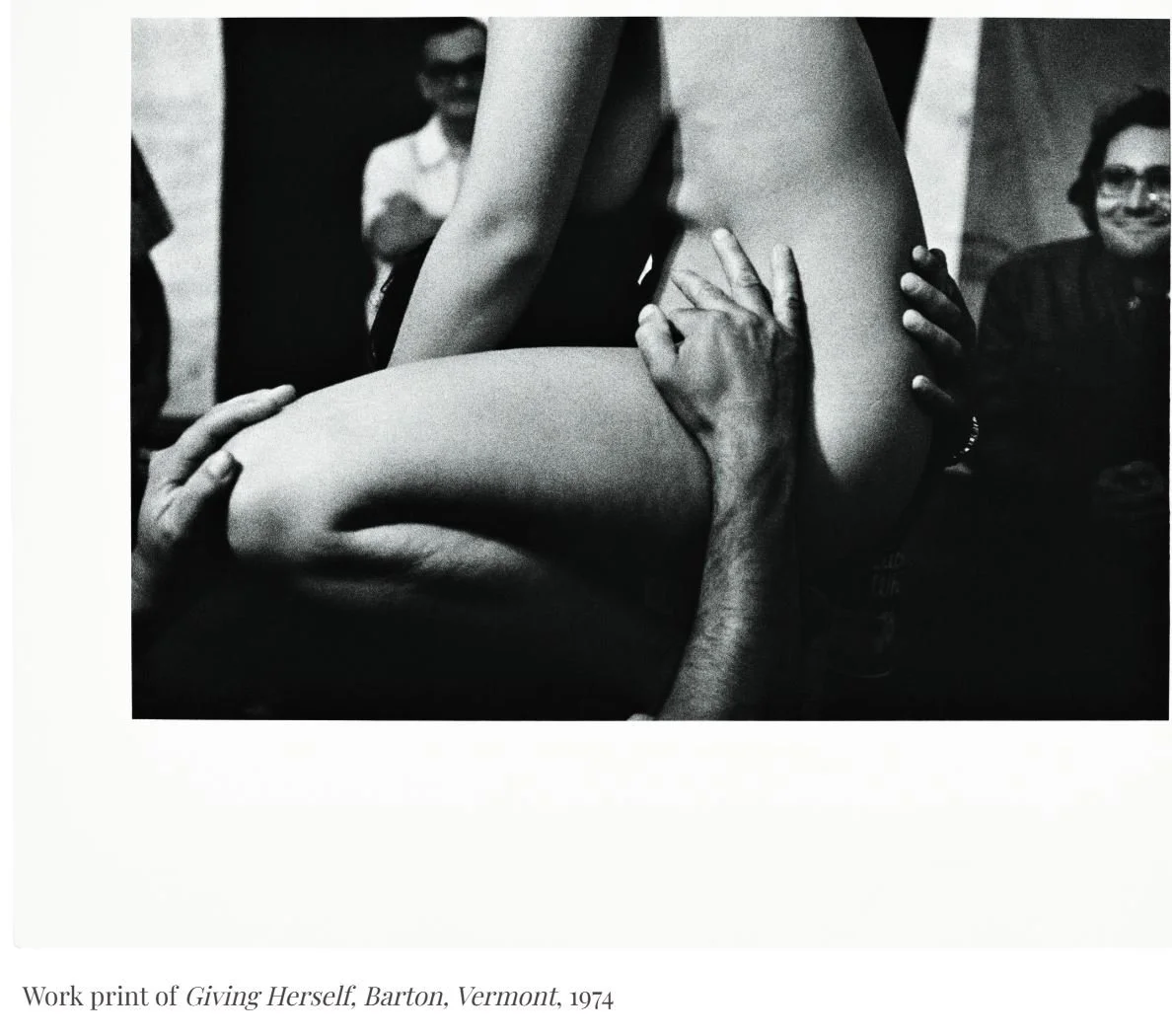

There’s the one who views the strippers as “background noise,” like the businessmen who would just come in pairs of two to my old club to drink and talk; the one who feels that we are being generous and giving a gift to the audience (“they’re making people happy”); and the creep who thinks it is okay to touch a dancer without their consent: “It’s not what you do, it’s what you get caught doing.” While certainly I do agree with Anna Biller’s assumption that the world of carnival strippers was likely “rough,” I differ on the reasons.

Although she uses two side-by-side black and white portraits of a dancer named Lena to emphasize the way in which women in the sex industry get “used up” in a short amount of time – Biller erroneously marks the photos as being one year apart, they are in fact three seasons of dancing and two years apart, and neglects the many other photos of Lena present in-between the two time periods – I think that life on the road, moving camp between towns every three-to-five days and sleeping in caravans and motels, must have been only some of the difficulties associated with this form of work.

Personally, as a dancer I would feel exhausted from endless nights of competing for clients on the front of a presumably rickety collapsible truck-stage to the repetitive sound of “Love Train” by the O-Jays (as you hear in the background of one of the audio tapes Meiselas has in the online exhibition for Carnival Strippers) in the hopes that I would secure a majority of the men in the crowd’s attention, who it appears would all have to collectively agree that I was the sole dancer they wanted to see in the private interior tent behind the mainstage (this is the practice as described by one of the dancers, Lena). It is one thing to be in a private alone with one, two, five or even ten men as the space allotted in my old club – it is quite another, as Lena described, to have to control alone with just your power and wits as an experienced worker a tentful of forty men: “It’s a tough life. You need strength and character. And when they come in, it’s up to the girl. She’s got forty guys in there. They could tear her limb from limb.

She’s got to control them, keep them back, and all she has is her wits and talents. The men can’t see it for what it is. The women look at it as being revolutionary – for the first time in their lives to say, ‘I’ve got you eating out of the palm of my hand.'” Particularly if you were a dancer doing extra full-service work to increase your wages, as Meiselas documented, I imagine that the stress of simultaneously maintaining such a large crowd would have been astronomical. My hat goes off to workers so thusly talented, and to all retired carnival strippers everywhere.

empress mirage, also known online at thepasteldomina, is a writer of smut and cultural commentary. she is a former fssw, bondage model, and stripper; she now creates online content as a findomme and living goddess. she is the creator of the 'sex/work & magic digest' newsletter on substack, which you can read at thepasteldomina.substack.com . find her on x: https://x.com/pasteldomina and blusky: https://bsky.app/profile/thepasteldomina.bsky.social