Dressing Dykes: A Brief History of Lesbian Fashion Signals

Make it stand out

In fashion, it’s not just the big things that are important, but the details. This is no different when it comes to lesbian style, especially at times when lesbians faced social and possibly legal consequences if their lifestyles were public knowledge. In these cases, the little things are sometimes the most important part of an outfit. This still rings true today - sometimes, a person might not be out, or might not feel safe to be so in a certain place or situation, and need to use their accessories to subtly represent their true self.

Fashion signals are how we reach out to each other in more minute ways. We’ve all heard of the phrase “actions speak louder than words”, but perhaps we should change “actions” to “clothes”.

Signals have a long history in lesbian fashion - but let’s start by rewinding one hundred years and looking at the 1920s. “What was a lesbian fashion signal in the 1920s, then?” I hear you ask, and the answer is: monocles. The singular eyeglass, invented in Germany in the early 1700s, existed at first as an accessory for aristocratic men. During the Victorian era its popularity waned, but by the turn of the 20th century it had begun to climb back into fashion and this time, on the faces of women.

Fig. 1: Brassaï. Photograph of lesbians at Le Monocle. Paris, 1932.

The monocle reached its fashion peak in the 1920s, worn by modern, stylish, rich young women in cities like London and Paris. But it had a double meaning: It signalled not just the daring of its fashion-conscious wearer, but the possibility that the women whose eyes it covered might be affiliated with a community other than modern socialites. I mean, of course, a community of lesbians.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Lesbian signals, like Doc Martens, can only succeed if they are mostly or only being worn by lesbians. If they become a trend in mainstream fashion, they no longer work.

Una Troubridge is one of the lesbians most associated with monocle-wearing. She was a Lady by marriage as well as the long-term lover of Radclyffe Hall, author of the first lesbian novel, The Well of Loneliness. When Una first welcomed the monocle into her wardrobe, she wasn’t so out of the ordinary - her style signalled wealth and modernity more so than sexual inversion (as homosexuality was known at this time). However, this soon changed.

As the 1920s came to a close, lesbianism was becoming more publicly visible. This meant that the fashions associated with it were also becoming more obvious. The Well of Loneliness had been published in 1927, and banned in the UK soon after; attention had been drawn to the book because of the scandal associated with it, and the fashions presented in its pages were suddenly viewed with suspicion. Monocles continued to be worn only by those most dedicated to them - which is how they became the emblem of Parisian lesbian bar Le Monocle. Now, we have fabulous photographs to look back on from Le Monocle, which were taken by photographer Brassaï in 1932. They show groups of lesbians flirting, dancing, drinking, and wearing monocles. Even when it went out of popular fashion as an accessory, it continued to be beloved by lesbians. It was a signal, and a symbol of their difference and their culture.

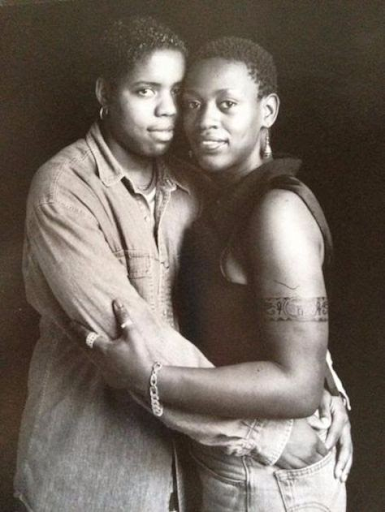

Keisha and Lia by Joyce Culver, 1995.

But the monocle only ever really took off in more upper-class lesbian circles. What about everyone else? Around the same time - between the First and Second World Wars - another lesbian signal, favoured by working class lesbians, was the pinky ring. Fashion historian Katrina Rolley, in her interviews with British lesbians about their fashion during this time period, was assured by two of her participants that pinky rings had been a symbol of lesbian identity. Both had worn them throughout their lives. They were also both working class - the third woman interviewed by Rolley, who came from an upper-class background, didn’t mention pinky rings at all.

And the pinky isn’t the only finger that’s been commonly bejeweled as a lesbian symbol. The thumb ring also has lesbian connotations, though these are more recent. Largely related to queer women in pop-culture - there’s definitely photographs of Kristen Stewart wearing a thumb ring floating around - it’s an accessory that never seems to have any deep analysis. Yet, it crops up time, time and time again. A cursory Google results in discussions on pages like Reddit and Urban Dictionary insisting that wearing a thumb ring equals lesbianism. Clearly, it’s an association that slipped into the popular psyche at some point or other. I’ve even recently heard that white thumb rings are springing up as a trend for queer women on TikTok, so as to be able to recognise one another off of the platform.

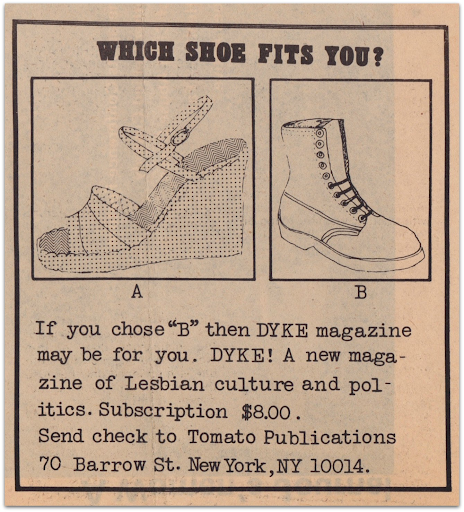

Rings and monocles are both additions to an outfit, accessories that are slipped on to adorn and, it seems, to signal. But sometimes, a signal can be less an accessory and more a kind of garment - a certain kind of shoe, perhaps. ‘Sensible’ footwear like sturdy boots, or possibly practical sandals, began signalling lesbian identity when worn as part of a wider anti-fashion ensemble. Ever wondered who made Doc Martens so popular? Yep, it was lesbians.

In the 1970s, lesbians were in the public and political sphere more than ever before, part of the Women’s Movement and Gay Liberation, and then as loud, lesbian activists. A new kind of dress code formed, far from the subtleties of the pinky ring or the extravagance of a monocle in the 1920s. To stomp around marches and meetings with the most practicality, it made sense that big boots were taken up by so many in the lesbian community. And, though lesbian feminism in this period on the whole scorned butch/femme fashions that had been more popular in the mid-century, big boots have always held a space on butch lesbian feet - especially the blue collar butches who wore them to their jobs.

While not all lesbians, of course, would have been wearing Doc Martens or other kinds of army-style boots even at this time, it was very much a recognised signal. Another fashion historian, Reina Lewis, wrote an article in 1997 called ‘Looking Good: The Lesbian Gaze and Fashion Imagery.’ In it, she bemoaned: “How to look fashionable and move with the changing trends, while still signifying as lesbian? At one time it was relatively easy: you wore whatever you wanted and combined it with big shoes or boots. But then everyone started wearing Doc. Martens and footwear’s lesbian coding was undermined.”

Lesbian signals, like Doc Martens, can only succeed if they are mostly or only being worn by lesbians. If they become a trend in mainstream fashion, they no longer work. Sure, they might still be a lesbian stereotype, and lesbians may still be wearing them, but any certainty in the situation is stripped away. And yet, lesbians still want to recognise each other - this much is evident if only in the comments of my TikTok videos, where lesbians and other sapphics write that they, too, own a pair of Doc Martens, or that they’re off to buy a pinky ring right now! The solution, then, is to stay one step ahead. This is easy enough: queer fashion is usually a way in front of the fast-fashion trends that follow after it. We might not be able to do anything about the subsuming of our trends and signals into the mainstream fashion ocean, but we can keep going. The future of lesbian signals is ours, if we take it.

Words: Eleanor Medhurst | Illustration: Kate Guihan