Glitch Art, Digital Decay and Why TikTok is Celebrating Imperfect Technology

Words: Izzy Bilkus

When I was growing up in the 2000s, I’d shut myself away with the family computer and make my Sims 2 versions of Bella and Edward from Twilight make out. For hours. The game would eventually start to overheat and bug out – the screen freezing, faces shattering, bodies jittering like haunted mannequins. At the time it was mortifying, a literal glitch in my secret fantasy, but looking back, there was something strangely alluring about it: the moment when the screen collapsed under the weight of my teenage melodrama, dissolving into a mess of digital debris.

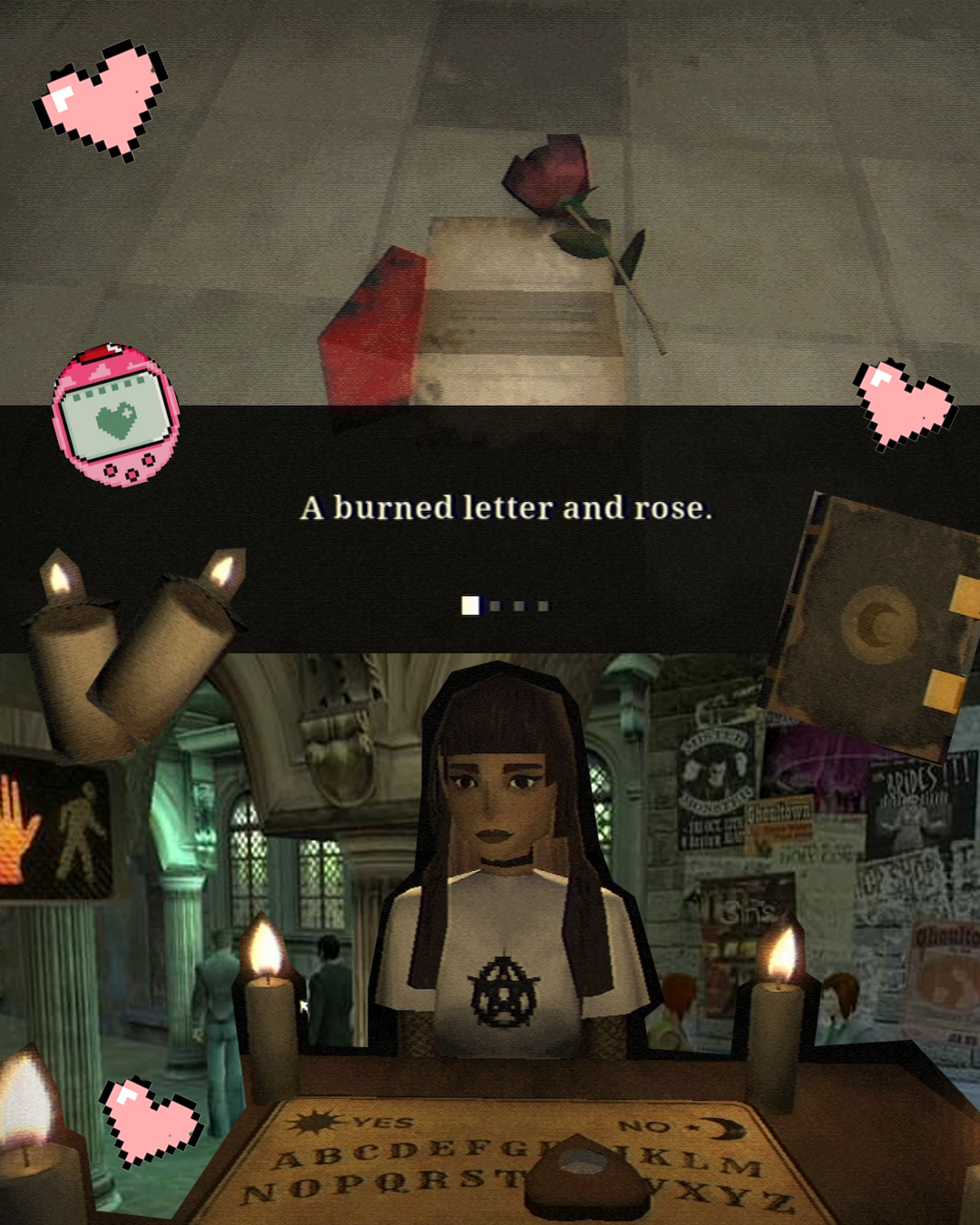

That same aesthetic – the shimmer of broken worlds and obsolete media – is resurfacing online, through TikToks of low-poly montages and eerie edits of early 2000s horror games like Silent Hill, Resident Evil and Vampire: The Masquerade – Bloodlines. Once dismissed as graphically poor, they now evoke an uncanny nostalgia. Stiff NPCs and patchy textures – the very markers of technological failure – are being reimagined as aesthetic choices and emotional landscapes. These fan cam-esque walkthroughs of cold, abandoned towns read like elegies for the weirder, darker days of being online, inviting us to reflect on what it means to live among the ruins of our own technology.

If nostalgia usually smooths the past into something glossy and warm, this particular strain is doing the opposite. There’s an unsettling familiarity in watching these virtual worlds stall or dissolve into static. The comments under these clips read like diary entries for the terminally online: “Take me back”, “Why does this make me want to cry?”, “I was there, but I wasn’t.” It’s not the games people miss, but the old technology that felt more human in its imperfection.

The videos play out like bite-sized hauntologies. The fog settling over the barren town of Silent Hill, the flicker of a fluorescent streetlight in Bloodlines, the laggy trudges through Resident Evil’s mouldy corridors – all of it becomes a language for remembering not what was lost, but what it felt like to lose it. Platforms like TikTok have turned the aesthetics of glitch into ambience, recasting outdated graphics as collective memory.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

There’s a charm to this ghostliness, a sense of returning to the early 2000s when the virtual still felt new and mysterious. Even contemporary horror games are mining this feeling. Titles like Fear the Spotlight (2024) and Fears to Fathom (2021) deliberately mimic the awkward animations of their ancestors. The flickering CRT filters, the uncanny stillness, the sense that the whole thing might crash at any second. In Fears to Fathom, the horror lies in the banal domesticity of its spaces. Fear the Spotlight, with its block-like avatars and washed-out textures, collapses the distance between retro glitch and present-day paranoia. Players don’t just revisit the past; they inhabit a simulation of it, built to feel like a memory malfunctioning in real time.

“Artists are treating error as subject, celebrating corruption as the defining visual language of our time.”

This fascination with degradation isn’t confined to gaming; it’s cropping up across contemporary art. Martine Rose and Sharna Osborne’s 2024 video work Everything Must Change is a love letter to corruption. It’s a grainy fever dream of VHS clips that bridge the worlds of design, music and performance. Its warped visuals and warped logic feel ripped straight from a melting hard drive and mirror the psychic noise on our feeds. Over at Sadie Coles HQ, Arthur Jafa’s new exhibition, ‘GLAS NEGUS SUPREME’, is doing something similar. It features a video work of an over-exposed Prince performance on loop, capturing the same disconcerting allure and sense of cultural entropy as these gaming edits, where the future looks blurry and the past won’t stop buffering.

In film, too, the underground horror genre is rife with technological unease. Skinamarink (2022) turns a child’s-eye view of an empty house into a grainy nightmare. Obelisk, an ongoing analog horror series on YouTube, riffs off the tropes of cryptid storytelling. And in Munich, the Pinakothek der Moderne’s 2024 exhibition ‘Glitch’ laid it all out: artists treating error as subject, celebrating corruption as the defining visual language of our time. Even the ‘brainrot’ side of the internet – nonsensical memes, endless scrolls of AI slop and sensory-overload content – fits into this lineage. It’s the glitch aesthetic stripped of nostalgia, where pure atrophy masquerades as entertainment.

Artists have been tracing this trajectory for decades. Nam June Paik, who pioneered the use of television and video in art, was infamous for his TV sculptures that flickered with the same spectral energy. Lynn Hershman Leeson, whose work explores surveillance, mass media and voyeurism, creates digital avatars that expose the fragility of identity inside the machine. And Turner Prize-winner (and patron saint of haunted media) Mark Leckey’s ghostly video assemblages capture an impermanence that feels transcendent, and the eerie persistence of obsolete media in the digital age. Together, they chart a genealogy of glitch – a line that runs straight through to today’s trending video game clips. What ties it all together is an obsession with the moment the system falters, when technology reveals its own mortality. The internet’s latest niche obsession isn’t about looking back with longing; it’s about watching the surface crack and finding beauty in what leaks through.

This revival of digital decay also reflects a disillusionment with the slickness of contemporary tech culture. Today’s media promises seamlessness with perfectly curated algorithms and polished interfaces. But the glitch aesthetic is pushing back, reintroducing error into spaces that have been aggressively optimised to keep us scrolling. Maybe that’s why these horror montages feel so oddly moving. They remind us that every file, every feed, and every world we create online will one day be obsolete, and that maybe there’s comfort to be found in the rot.