Gunter, Whimsigoth and How Portraying Historical Witches as Empowered May Be Harmful

Words: Zara Afthab

Make it stand out

Over the last few decades, public perception of the witch in most Western societies has shifted away from her antagonistic roots to signify empowerment and power. Saccharine phrases that allude to the purported radical, feminist quality of the witch, such as “We are the granddaughters of the witches they couldn’t burn,” are plastered on placards or lazily printed onto t-shirts and tote bags. In the 90s, films and television like Practical Magic, The Craft and Sabrina The Teenage Witch positioned the witch as a girl-next-door type that happened to possess powers and had a penchant for sarcasm, apothecaries and black cats.

More recently, mainstream witch stories fall into the “good for her” genre in which a newly emancipated figure exacts her revenge on a man who has wronged her and, by extension, exacts symbolic revenge on the patriarchy. In most cases, the Western witch is also represented as a conventionally attractive, white, suburban, middle-class woman, sweeping under the rug the relationship between witchcraft and North America’s indigenous population. Its feminist reclamation also often glossesover the darker roots of the witch, the gendered politics at play and the reality of witch trials that are still prevalent in some parts of South Asia and Nigeria.

The widespread reclamation of the witch that began in the 1960s and 1970s with anti-capitalist books such as Silvia Federici’s Caliban and the Witch has, with extreme vigour, come to represent girl power, empowerment and, to some extent, sexual liberation for 21st-century practitioners of witchcraft, who often congregate on Instagram or Witchtok. In the European and North American reclamation of the witch, aesthetics are paramount, and one signifies their witchy or ‘whimsigoth’ status through gemstones on their window sill, velvet dresses and layered jewellery adorned with cosmic charms.

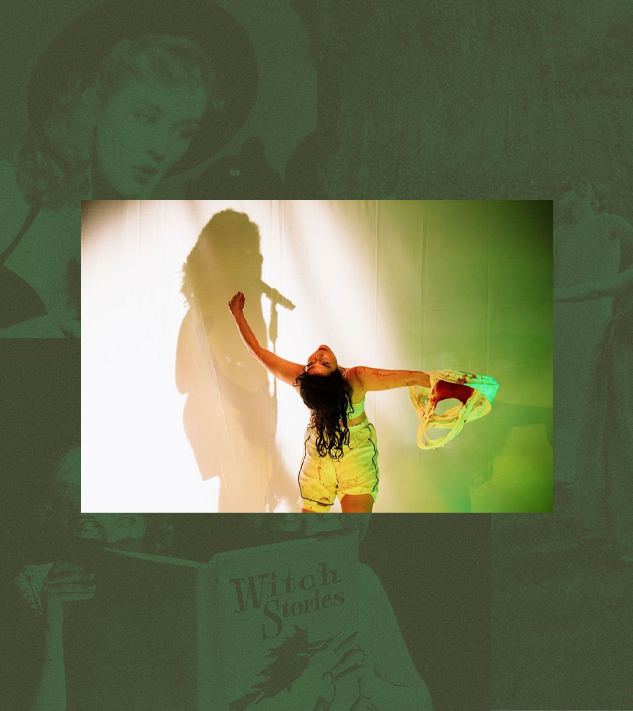

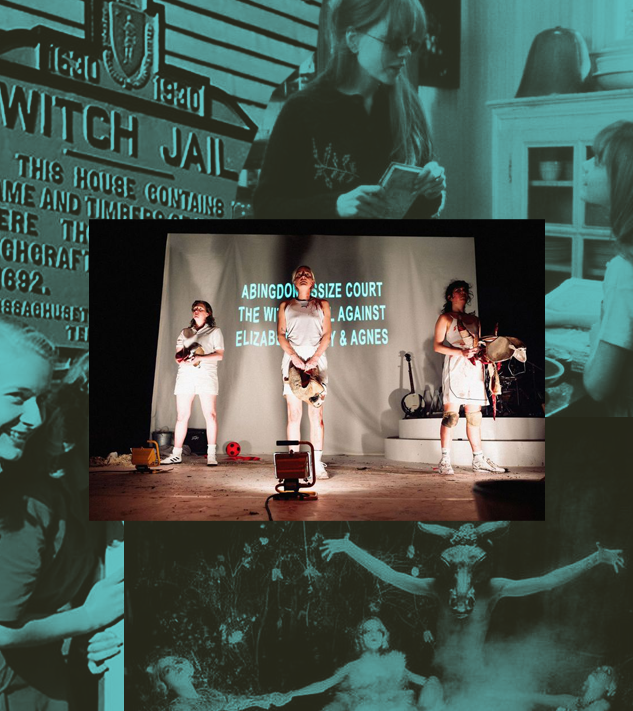

I walked into the Royal Court Theatre earlier this week to watch a piece of gig theatre on ‘murder and witchcraft’ titled Gunter, expecting a whimsigoth revenge plot with flattened messages of empowerment play out on stage. However, what I received instead was an exciting, surprisingly scruffy yet equally gorgeous subversion of a historical drama that delved into the archives of Anne Gunter’s witch trial of 1604 to put forward the grim reality surrounding the persecution of “witches,” patriarchal power dynamics and family abuse during the period. The theatre company behind Gunter, Dirty Hare, made up of co-creators Lydia Higman, Julia Grogan (both of whom also performed on stage), and Rachel Lemon, who directs through perfectly timed comedic punches and a captivating score composed by Higman, unpack the false perception of the witch in early modern England.

The play opens with Brian Gunter, one of the wealthiest men in the village, murdering two brothers during a football game - a sport Brian Gunter touted uncivilised- and manages to evade persecution for his actions by blaming his reaction on the boys and their mother, Elizabeth Gregory. In retaliation, the vocal mother took to the village market, chipping away at Brian Gunter’s public opinion by calling him an abusive, greedy murderer. Subsequently, he accused Elizabeth of witchcraft, leveraging his daughter Anne Gunter's illness as supposed evidence of bewitchment and the ongoing persecution of witches between 1550 and 1700 in his favour. The case leads to a legal battle that reaches the court of King James I.

“Throughout Gunter, the focus is, however, not on the alleged power they possessed as outliers but rather on the strict gender norms at play.”

In what Jamie Doward referenced in The Guardian as the “great age of witch trials,” women in Europe who were regularly accused of tapping into satanic forces and possessing the otherworldly power to heal and destroy were the enemy of the church and the state. Throughout Gunter, the focus is, however, not on the alleged power they possessed as outliers but rather on the strict gender norms at play.

In my chat with Dirty Hare, Higman shared how the company wanted to do justice to the women who experienced local abuse and victimisation from people like Brian Gunter rather than present them as supposed feminist icons. “There’s this interesting paradigm shift in terms of the cultural position of witches today that symbolises both subversion and power. While I think it is true to some extent in the early modern period, the power these women held did not stem from witchcraft,” Higman explains. “The fact that there are no real witches in this story is a testament to the fact that the only thing that was operating in this story was the fragile male ego and the dominating power of the patriarchy that led to, in this case, the abuse of an outspoken yet grieving mother.”

You come out of Gunter realising that witches throughout history may or may not have been women who hexed their neighbours, but they were definitely women who, in some shape or form, defied their gender roles. The witch in this story, Elizabeth Gregory, refused to be the stoic, silent grieving mother and, instead, was vocal in her resentment of Brian Gunter and demanded justice for her dead sons.

Throughout history, “witches” have disrupted power structures, and in response, they’ve been punished. In Caliban and the Witch, Silvia Federici asserted how witches cause trouble for the smooth functioning of a patriarchal capitalist society, writing that witches were “the heretic, the healer, the disobedient wife, the woman who dared to live alone, the obeah woman who poisoned the master’s food and inspired the slaves to revolt.”

Grogan revealed in our interview that even before the events relating to Brian Gunter unfolded, Elizabeth was notoriously outspoken. “In our research, we found out that she was a known scold who would swear and curse, so she was primed before her accusation of having a reputation for being rebellious. Throughout the play, she’s oscillating between the weakness of what it is to be a woman who's lost her children and the strength she summoned up to confront Brian Gunter while everyone around her is trying to silence her.”

This idea of the witch as merely a ‘bad woman’ was emphasised further by Higman’s songwriting, delivering a climactic ending to the play. With lyrics plainly stating that the persecuted were ‘bad women,’ we hear how it was these women and the paradoxical nature of their existence, and not spellbinding curses, that were threatening to the social order. In Learning from Witchy and Wayward Women, Alys Weinbaum succinctly dissects the phenomenon, writing on how witches were punished due to their acts of refusal, “Ranging from religious heresy to non-procreative sexuality to infanticide, which threatened to abort (sometimes literally) what Marx described as capitalism's ‘bloody birth.’ They were put to death because their witchy ways of being in the world were considered dangerously contagious, their project of subversion transferable to future generations of wayward women who might, in their turn, do as the witches had: Resist!”

As the lights dimmed on Gunter, it was this feeling of resistance inherent to the bad woman who deviated from her gender and quiet moments of subversion that left me feeling giddy and not the ‘good for her’ trope. And while it didn’t help that Fiona Apple was playing in the background, compounding sentiments of angry insurgency bubbling inside me, watching this play was a marvellous reminder of how deeply crucial fixed gender roles are to the state, social reproduction and, by extension, capitalism.