Insights on Labiaplasty From People Who Have Had One

Words: Tara Jones

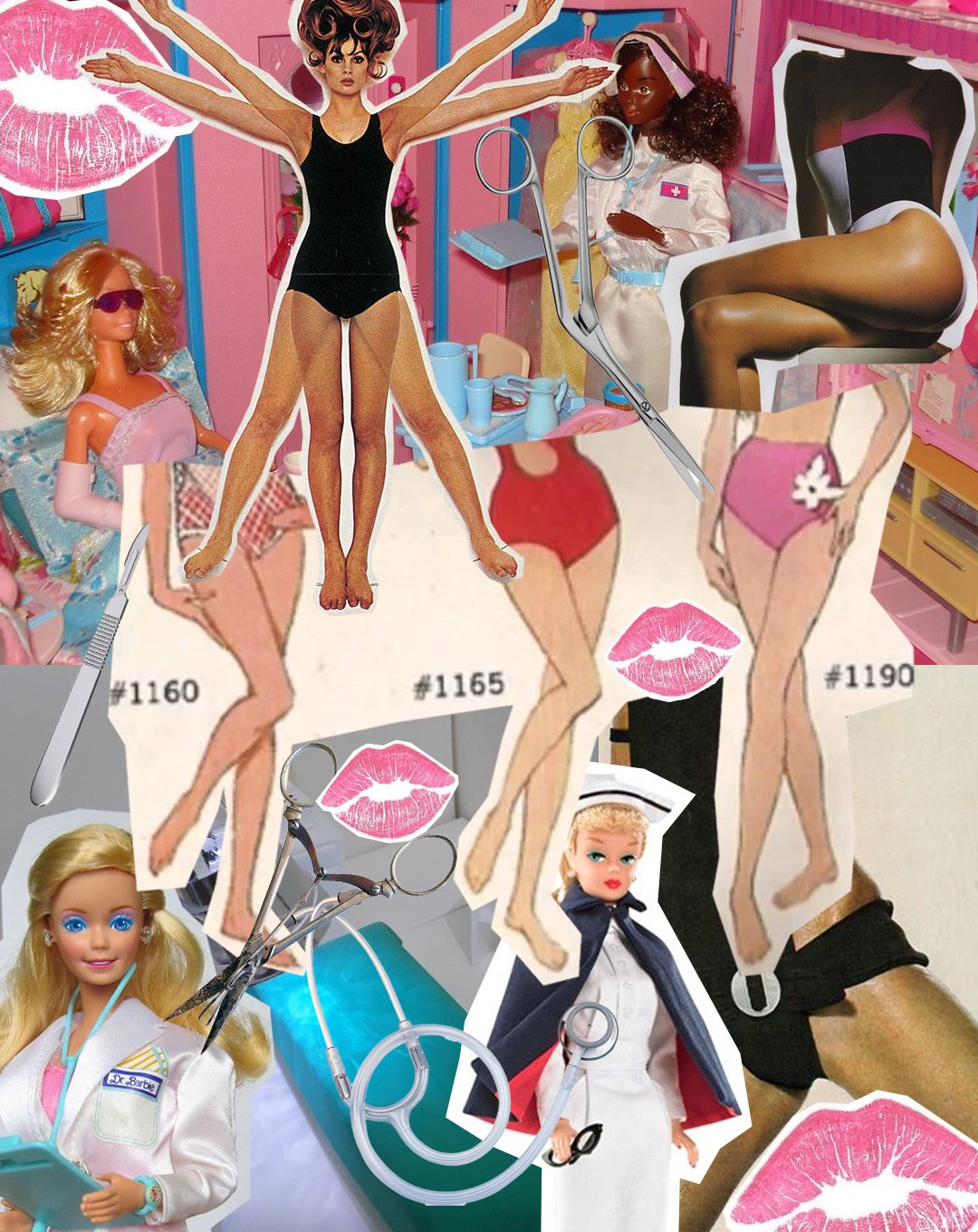

“I was seventeen,” Victoria* tells me, recalling one of her earliest sexual experiences. She had been dating a boy for a while when they decided to have sex. Afterward, as she went to pull her underwear back on, she noticed him staring at the soft bulge beneath the fabric. “I wasn't a fucking Barbie, it wasn’t completely flat. I remember him saying ‘Why does it look like that? What is that?’”

This brief, cruel moment was one of the first memories on the list of experiences that led her to consider a labiaplasty. There were other influences, like the early porn consumption that convinced her “labias were basically supposed to not exist.” Ultimately, she ended up keeping the lips native to her body. The reasons behind her desire for a different vulva, though, speak to how young people with vulvas come to see their anatomy as flawed.

A labiaplasty involves trimming and reshaping the tissue of the labia minora, or inner lips of the vulva. Beyond the surgical steps, there is the more nuanced terrain that I’m interested in: the motivations that push someone toward labiaplasty, and the forces that pull them back, since according to the most recent data (2023), the number of labiaplasties performed globally has nearly doubled in the last ten years.

The rationale for seeking a labiaplasty can generally be sorted into two categories: comfort and aesthetic. With the former, people primarily seeking relief, their reasons tend to be considered medically necessary. Longer labia can make physical activity such as walking or running uncomfortable, chafing is a factor, and even showering can require extra effort, increasing vulnerability to vulvovaginal infections. Some research suggests, however, that even those driven by comfort often carry aesthetic concerns as well.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Aesthetic motivations are largely shaped by cultural messaging. Even examining language like “minora” vs. “majora”, which quietly instructs that inner labia are meant to be short and neatly contained within the outer. Historically, limited public conversations about labia diversity meant that most of our models of “normal” vulvas were film and porn, where vulvas tend to be hairless, pink and tucked. It isn’t uncommon these days, though, to see people discussing “innies” or “outies” on TikTok, referring to how vulvas can range from those with shorter lips to those that protrude. And the more we talk online the more a truth becomes apparent before our very eyes, 56% of people with vulvas have “outies”. “Why does it look like that?” Victoria’s adolescent ex boyfriend asked, well as it turns out, most do.

“An elementary description of feminism would tell you, quite simply, that women have the right to choose. This was a right hard fought for in the context of voting, or employment. When we look a bit closer, we realise that choice isn’t always that simple.”

Internet culture has played an arguably more insidious role as well. In my conversations with young adults who either pursued or seriously considered labiaplasty, it became clear to me that the internet fed and sometimes created these desires. Porn was referenced in nearly all of my conversations, but people also pointed to how the internet normalized the idea of getting a labiaplasty. One interviewee even discovered on social media that she could get her labiaplasty covered by insurance, which prompted her to pursue it.

The conversation about labiaplasty mirrors that about plastic surgery broadly, one that is happening on social media, and is informed by social media. The gist is that these decisions don’t just happen in a vacuum. Social media disseminates new trends and insecurities in real time, and immediately provides the precise instructions on how you might go about “fixing” yourself.

An elementary description of feminism would tell you, quite simply, that women have the right to choose. This was a right hard fought for in the context of voting, or employment. When we look a bit closer, we realise that choice isn’t always that simple. Some women use their right to choose in ways that reinforce systems that oppress other women. Think of the female CEO who only promotes men in her workplace, as to look unbiased. Thinking big picture about the collective liberation of women is what makes the question of plastic surgery complicated. Is it truly “your body, your choice” if those choices perpetuate unrealistic beauty standards that other women will then be measured against? If your BBL contributes to the patriarchy, what does that mean for Botox, fillers, braces, makeup, or long hair? Where is the line between self-expression and surrender to the male gaze? And is it even fair to criticize someone for contorting themselves to that gaze if doing so improves the material conditions of her life?

Those who dislike “choice-feminism” might condemn plastic surgery altogether, and might assume that those who I interviewed who eventually decided against labiaplasty reached a similar ideological conclusion. Sometimes that was true, Elizabeth for example recounted a girls trip, during which all of her friends showed one another their vulvas and basked in one another’s beauty and variety. For Victoria though, the decision was far less ideological, it was financial. When she asked a parent about getting a labiaplasty, the answer was that they simply couldn’t afford it. This is the larger point: politics around liberation aside, there are larger systems at play, like privilege.

“I remember seeing my dermatologist, not too long after the procedure,” Adrienne shared. Sitting on an exam chair, anxious about concerns having nothing to do with her genitals, her doctor noticed a labiaplasty listed in her medical records. “She asked me why I had the procedure. From her phrasing and tone, I felt that there was some judgment… it made me feel like she thought the procedure was unnecessary.” Adrienne had undergone the surgery because the lengths of her labia were causing discomfort during sex, a reason that could be deemed medically necessary and, that she emphasizes, was not aesthetic at all. Still, she was met with judgment from another woman, and now feels hesitant to talk about her labiaplasty with people close to her out of fear of the same response.

Even if her motivations had been aesthetic, there’s a greater context. “Pretty privilege” isn’t just something to brag about when you get a free drink at the bar. Like whiteness or thinness, meeting beauty standards can materially shape a woman’s life within systems designed to oppress. So why are we quick to judge women for aspiring to advantages in a system they didn’t build?

Sex can be a particularly oppressive site, a playground for interpersonal power dynamics and an act already shrouded in taboo. This was evident in the accounts of those I spoke with who detailed instances where they were shamed by their male partners about some of the most private parts of their bodies. The decision to pursue, or not go through with, a labiaplasty is rarely simple.

While rejecting beauty standards can be brave, radical even, not everyone has the same starting point; privilege shapes the choices we can even imagine making. The fact that so many feel compelled to alter their vulvas is a reflection not of personal weakness or poor judgment, but of the societal demands constantly swirling around bodies and desirability. Choice feminism doesn’t resolve that really, but blaming individual women for engaging with these expectations misses the point.

Instead, the conversation could shift toward empathy, while continuing to interrogate how these procedures are normalized and popularized, and what that says about society’s obsession with our bodies.

*All names were changed