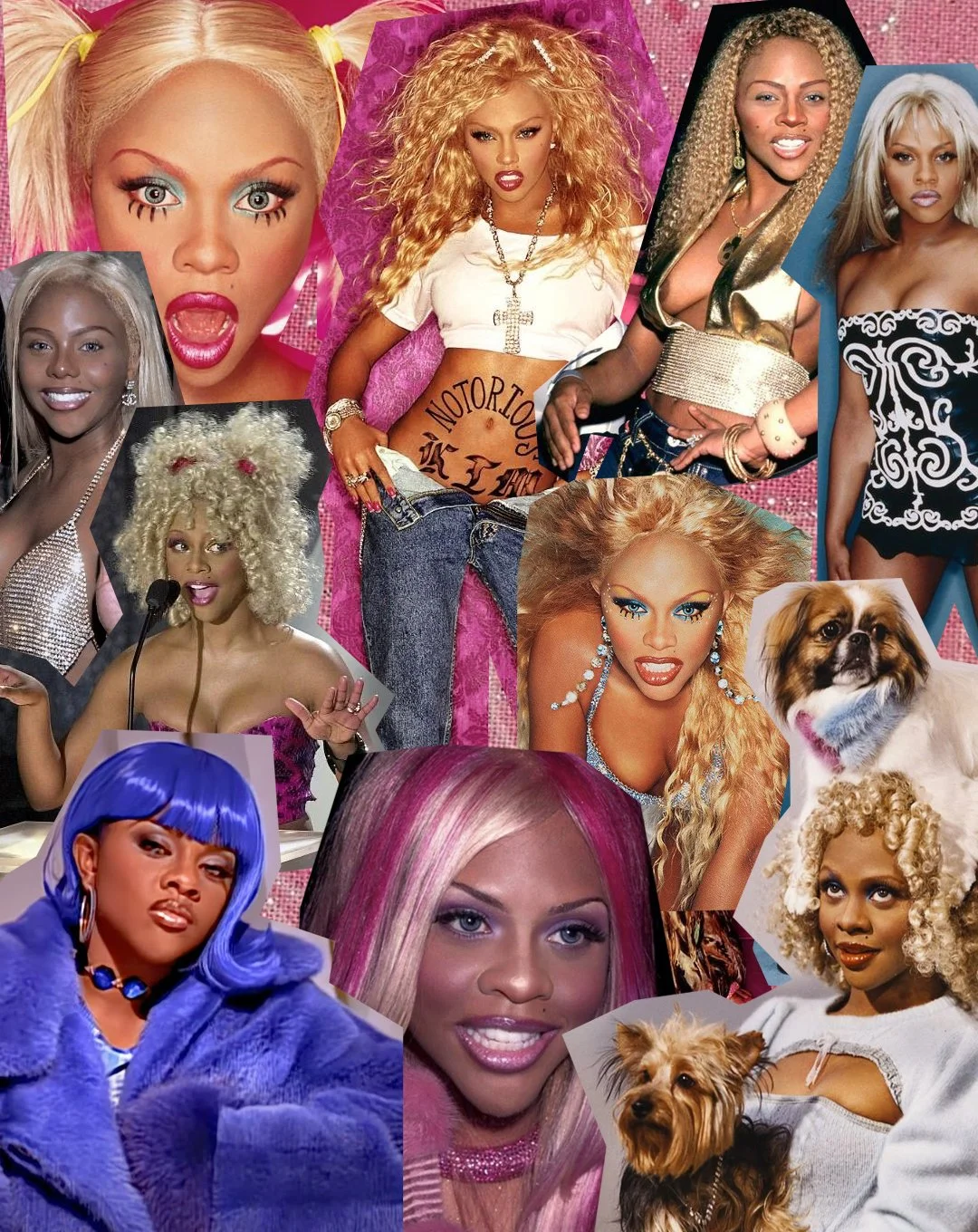

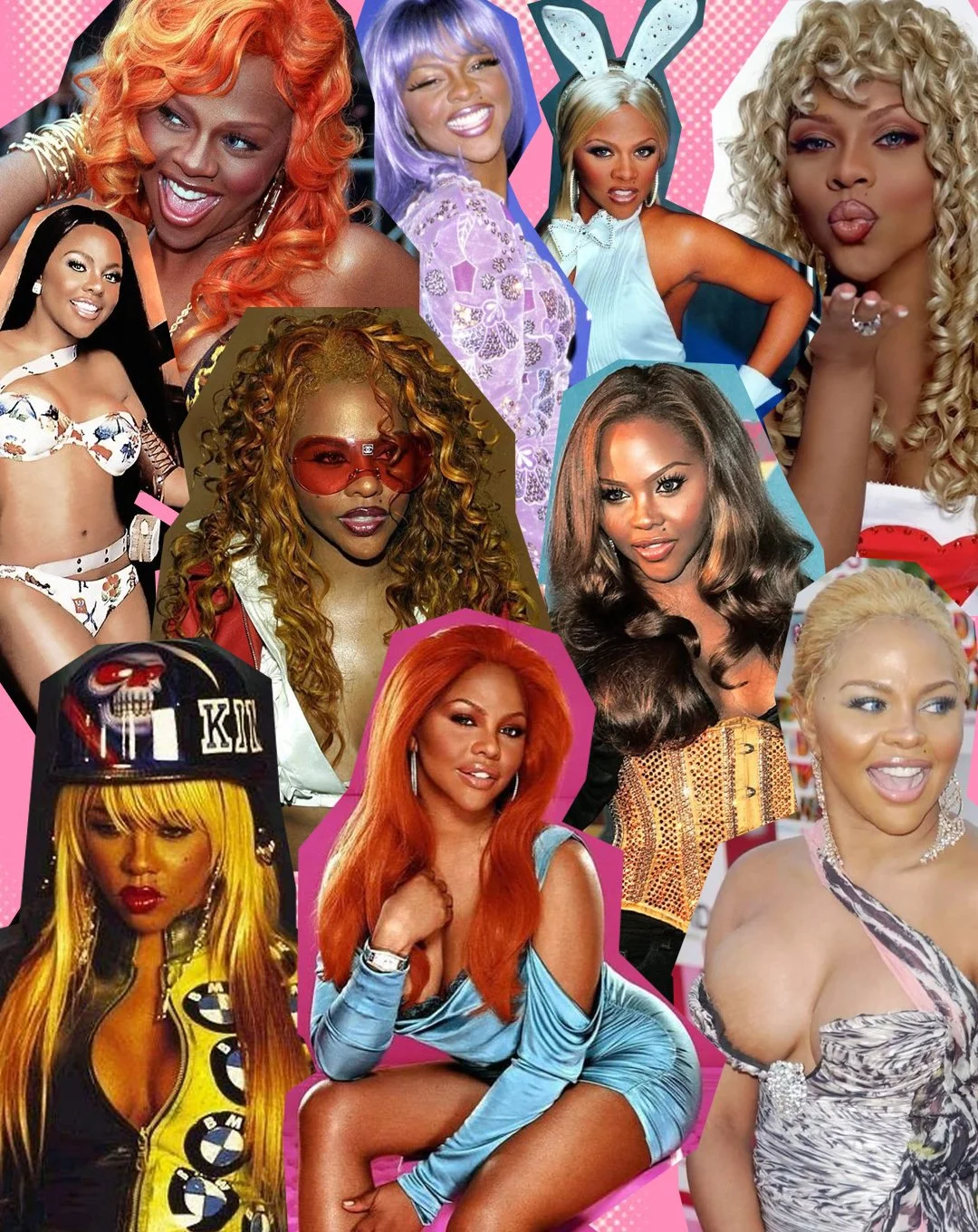

Lil Kim, bell hooks and How We Value Love

Words: Camila Valle

Make it stand out

Seven months after the release of Lil’ Kim’s stunning debut album Hard Core, bell hooks interviewed the rapper for the May 1997 Paper cover story. Rereading it almost three decades later, it still makes me well up with the intensity of all we owe her, how brave she’s been, and how callously we’ve ricocheted our own shit onto her to see what would stick. It also makes me feel, fiercely, what Kim has made me feel since the first time I heard her rap: smart and raw and funny and what the fuck are you looking at???

In the interview, hooks seems to insist on a two-pronged, but related, line of questioning: Is your work about freedom or about getting paid? Are you a male fantasy or a liberated woman? What we’ve put on Kim for the entirety of her prolific, magnetic, thirty-year career is this demand – this impossible trap of a demand – to finally settle the debate. I love Kim for her art and for her answer to this interrogation: “Both.” For me, it’s the only reply that lands.

Something that comes with the Kim territory, the gnawing subtext underlying these probings, is the idea that Biggie made her. That he wrote her lyrics, picked the promo photos, constructed her image, and all she did was be a kind of cooperative sexualised puppet. Or, as hooks put it: “This 21-year-old has gone where others have not been able to go, ’cause she’s got the right dudes behind her.”

In this push and pull, feminism is often portrayed as what’s at stake – is someone like Kim setting women’s liberation back or advancing it? But feminism has always been about the indigestible. Its use as a clarifying force in my life and in the world does not come from a power to neatly categorise us between ‘liberated’ versus ‘male gaze-pilled’. There is more to work through when it comes to the specific ways that one is oppressed – this phrenic, libidinal, intricate brew of our individual and collective gendered experiences. To deny this does us all a disservice.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

The critic Édouard Glissant writes about our “right to opacity,” doing away with the insistence on our own and others’ self-rationality:

[It] is barbaric to impose one’s own transparency on other people.… If I don’t accept my own opacity for myself, I’ve essentially defeated myself, but I can accept my own opacity and say: I don’t know why. I don’t know why, but I detest this person or like this other person…not for any particular quality or reason, but just because I do.… Why wouldn’t I accept it on other levels? Why wouldn’t I accept the other’s opacity?

Or, to bring Glissant into conversation with Kim, I don’t know why I feel sexy when I do, why I feel in control of my body sometimes and not others, why I feel legible in leopard-print lingerie, or misunderstood in leopard-print lingerie, or both. Of course, desire is not politically neutral. Material forces matter; they are part of the equation. We are shaped by oppression, by sexism and racism and transphobia and so on. But our psyches, our selves, rich and infinite, are not reducible to such facile resolutions. Kim has always known this. She has shown us from the beginning.

And yet, in her interview with Kim and her book All About Love, hooks zeroes in on the corrupting power of greed and money, counterposing it with sexual and emotional freedom. Reflecting on her experience talking to Kim, she writes:

Everyone finds it difficult to resist the dictates of greed. Letting go of material desires may compel us to enter the space where our emotional wants are exposed. When I interviewed popular rap artist Lil’ Kim, I found it fascinating that she had no interest in love. While she spoke articulately about the lack of love in her life, the topic that most galvanized her attention was making money. I came away from our discussion awed by the reality that a young black female from a broken home, with less than a high school education, could struggle against all manner of barriers and accumulate material riches yet be without hope that she could overcome the barriers blocking her from knowing how to give and receive love.

hooks’s conclusion here betrays not only an affective rigidity, but also a lack of generosity. Kim isn’t just a set of circumstances, and she never denied an interest in love. She said, “I don’t have that,” and went into some of her painful history with men who mistreated her. “Guys used to tell me I wasn’t shit, I always gotta rely on them, like, ‘You ain’t shit without me. You always goin’ to need me.… You can’t fucking make it without me. You’re ugly.’”

“In the face of the prospect of always being dependent on unloving men, the drive to get paid becomes more concrete than ever.”

In the face of the prospect of always being dependent on unloving men, the drive to get paid becomes more concrete than ever. Yet hooks pits them against each other, as if money has nothing to do with women’s, particularly working-class women’s, independence, sense of agency, or the creation of conditions that allow them to feel free. As if the fight for women to be valued – yes, to get paid – for their work, both inside and outside of the home, hasn’t been at the forefront of centuries of struggles for liberation.

Say what you will about Kim (I’m sure she’s heard it all), but she taught me how to love myself and others, especially other women, in all of our inevitable contradictions and desires. That we are worthy subjects, worthy of pleasure and respect for exactly who we are, whatever that means, even if we don’t know it ourselves. Long live our opacities. Long live Lil’ Kim.