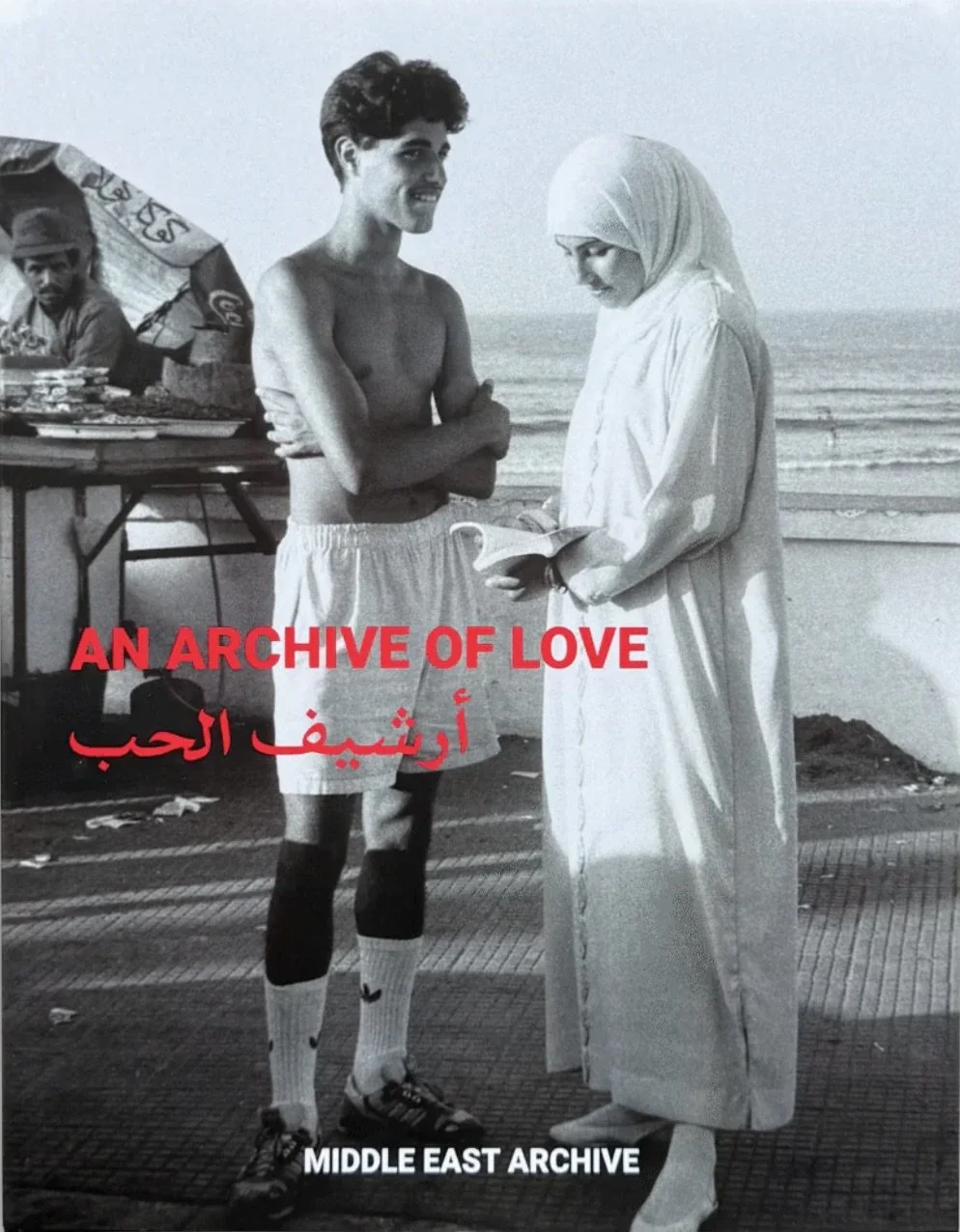

Middle East Archive is Exploring Love Through the Lens of Loss

Words: Sara Eldewak | Images via Archive of Love Volume II

The deepest grief in the Middle East and North African region is rooted in love - for land, for people, for a future still worth fighting for. In recent years, families and communities across the MENA have endured profound heartbreak and loss, leaving lasting marks on our hearts, homes, and collective memory.

We've witnessed this devastation unfold through genocidal violence in places like Palestine and Sudan, where the erasure of life and culture continues in plain sight.

As the violence escalates, so does our need to remember. What does it mean to grieve something ongoing? To hold onto memory when everything urges us to forget? An Archive of Love: Volume II considers remembrance as an act of resistance. Created by Middle East Archive, a publishing platform dedicated to reimagining and celebrating the visual narratives of the MENA region, An Archive of Love: Volume II is a photography book which features the work of photographers Myriam Boulos, Maen Hammad, Moises Sammam, Abbas, Mohammed Namoor, Charles Thiefanie, Amir Behroozi, Atia Darwish, Anthony Hamboussi, Scarlett Cotten, Fethi Sahraoui and many more. The volume is published with two covers. Including a limited edition, with 100% of its profit donated to support photographers and journalists on the ground in Palestine.

I sat down with Romaisa Baddar, the founder/curator of the Middle East Archive to discuss the new volume and its relevance during this time. She went in depth about how the volume was born from a collective mourning, offering a space to honor grief as a powerful form of love. Baddar explained to me “I wanted to connect to what people are feeling, the loss of a homeland. Involve as many independent photographers as possible.” While the first volume celebrated love in its many forms, this second chapter pivots towards love shaped by absence and through the lens of loss.

Can you give me a bit of background on the creation of Archive of Love, and the process of creating it?

Baddar: An Archive of Love was originally published in 2023, it was a book I wanted to make to highlight love in the region, and its presence in our culture through the photography I would find. When we were making the first volume, we understood love is a very broad theme and there is so much that falls under it. So we divided it into four categories at the time to cover what was apparent in the photographs we would find. We divided it into love for your nation, brotherhood/sisterhood, romantic love and love for your faith. It’s been out for two years and still resonates with many people. It’s one of our most embraced books, and I really love it as well. I think representation is really needed in our region.

So when it came to reissuing the first book, how did that come about?

Baddar: I remember sitting with the team and we were all thinking about it, and we wanted to kind of refine the book by adding new photos. But as we were making it there was thought that just popped up I guess, and im happy it did, we realized with love comes aftermath. Going through a loss, especially thinking about our region and how much it's endured, I wanted to honor love through the lens of loss and look at love through the glimpse of a memory.

An Archive of Love continues its heartfelt mission to collect the intimate and personal — letters, memories, reflections — from voices across the region and its far-reaching diaspora. But Baddar emphasizes it’s not a documentary, “We took a lot of inspiration from current events, and from what people are feeling like loss of your homeland but also photos that showed the remaining of love, like showing photos on the wall after people had left.”

How do you see grief as a continuation of love, rather than its absence?

Baddar: So I’m muslim, and when someone passes away there wouldn't be a one time funeral and you hold space for that. Their memory is always with us, even during joyous moments and occasions like Eid for example, we would remember a relative that passed away. We would always pray for them, and hold their memory so in a way, I believe that is grief continuing. Keeping photographs is a continuation of trying to keep what's lost.

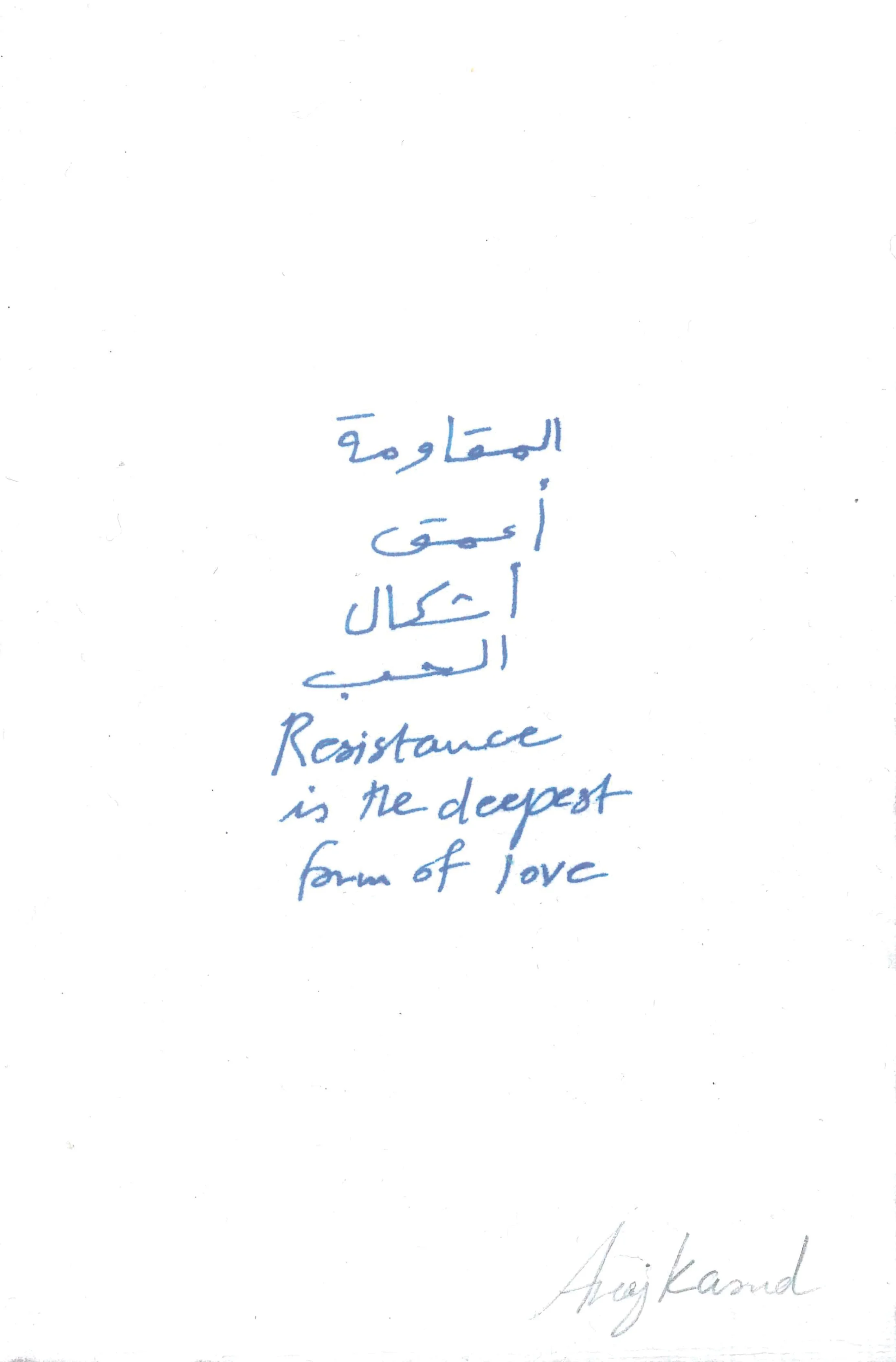

Why do you think it’s important to frame remembrance as resistance?

Baddar: Because that's all we have left. Most of us live in diaspora. I'm not Palestinian but imagine being Palestinian, never having the chance to return to your homeland and all you have is something as simple as a scarf for example. Holding on to that as simple as it sounds is a form of resistance because they are forcing it to exist. It's the only way it lives on, Existing proudly is resistance. Holding space for photographs, art, story-telling, passing down recipes, that's how we keep it alive.

What made you fall in love with photography, and do you think the Middle East Archive will play with different artistic mediums in the future?

Baddar: To me, I think photography is the closest thing we can get to catching reality. I always wanted to become a photographer, and curation is still a way for me to be in the field. In Archive of Love Volume I, there were many concepts in the first volume that needed more context, so I felt it was best to include a variety of texts. I felt like those words gave it justice. But as of right now and this book, we mostly use just photography.

In our conversation, Romaisa spoke with deep honesty about how her relationship to photography and how it's evolved — particularly in terms of ethics, representation, and responsibility. “I really learned more about my ethics in photography,” she reflected. “I try my best to gather information and make a judgment.” Growing up Muslim, she was always aware of the sensitivities around how her community is portrayed. That awareness shaped her approach behind the lens. She explains “There’s a responsibility there — I always try to stay respectful and sensitive. I ask myself, "Does this person want to be in a photobook?” What once may have felt like a distant consideration has now become central to her practice. She thinks carefully not just about how an image is made, but why, and for whom.

This self-reflection came into sharp focus during a project she considered last year. “I was going to make a book about the beauty of Palestine,” she said. “But it felt wrong — like I was creating a product that wasn’t directly benefiting the people on the ground.” That moment marked a turning point. “Right now,” she explained, “there needs to be urgent help in the region — and then, awareness.” For Romaisa, photography isn’t just a tool for storytelling; it carries a weight, a responsibility to serve the communities it depicts. The question she asks herself is clear and uncompromising: Who is benefiting from the art?

As we were finishing up our conversation, I asked Romaisa, What kind of legacy do you hope this Archive will leave for future generations of artists, mourners, and lovers? " She told me, “I’m eager to see work by our people,” she says. “It just feels different when it’s someone from your home country.” For her, the hope is that this archive and the broader visual language it contributes to will become the norm for how the region is seen, both in print and online. “I want the representation of our region to default in this direction,” she explains. “I’d love to see a future where someone travels to the region and is commissioned to photograph gardens, not just the fall of a regime.” She credits the growing body of work by independent artists who are shifting the focus from war and destruction to everyday life, joy, care, and resilience. “They center it around normal lived experiences,” she says. “And I really hope this continues in the future, I love to see it.” In that way, An Archive of Love: Volume II becomes more than a collection of photographs; it’s a collective act of remembrance, resistance, and radical love, reframing how the Middle East and North Africa are seen through the lens of loss, longing, and tenderness.