On Self Documentation: Your iPhone Notes App Remembers All Your Past Selves

Words: Rachel Hein

The words “apple cider vinegar” appear twenty-three times when I search my iPhone Notes app. Buried in a mélange of thousands of disjoined notes since 2012, the year I got my first iPhone, ACV has been a recurring character. It appears in sad grocery lists from my early twenties, copied and pasted meal plans plucked from the corners of diet culture hell, and to-do lists commanding myself to begin my day by drinking it mixed into a large glass of warm water with fresh lemon juice. Despite the good faith effort in each of these jots, not to mention the tenuous (at best) evidence to support claims about its health properties, I have never once purchased or consumed apple cider vinegar. Not once in twelve years.

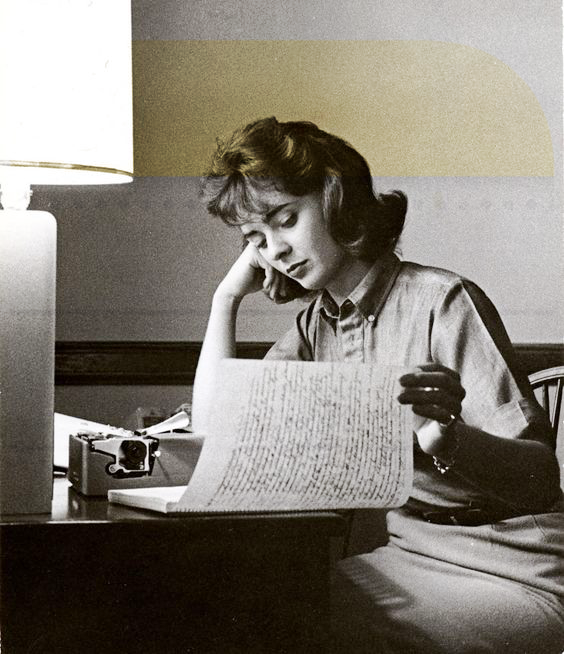

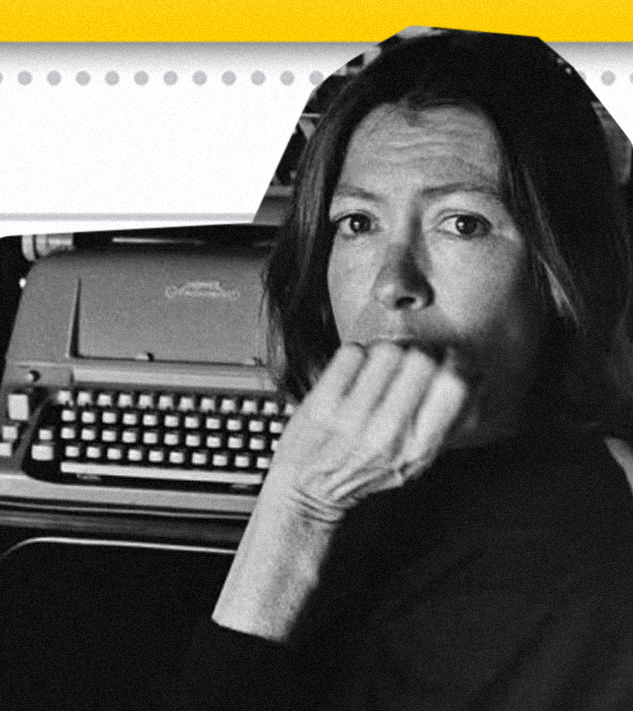

“Why did I write it down?” Joan Didion asks as she unravels the convoluted and compulsive nature of keeping a notebook in Slouching Towards Bethlehem. She surmises it’s a habit that “begins or does not begin in the cradle.” Her musings, often too obscure or erratic to be discernable to anyone but their author, ran the gamut: a log of the day’s chores and her accompanying emotional state, a quote from an older woman as they drank wine by the sea, disparate facts like “smart women almost always wear black in Cuba”, and a recipe for sauerkraut.

In an era where record-keeping and daily recounts happen online obsessively on democratised platforms offering a microphone - a public diary - to anyone and everyone, it begs the question: what are we writing simply for ourselves anymore? Where are the fragments of our observations, reflections, and abstractions only legible to our own eyes? Where are the negligible scrawls, fraught worries, or half-baked resolutions? Where is it safe for the most profound navel-gazing to exist without judgement, without the obsequious veil cast upon words for public consumption? I reached the conclusion that today, Joan’s hastiest, rawest, most unfiltered self would have lived freely only in the iPhone Notes app.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

For those of us afflicted with the compulsion to record and document any idea that feels worthy at a given moment, we find ourselves arranging and rearranging, trying to make sense of ourselves while governed by the percolating premonition that we’ll need to recall something we cannot access, or worse, simply don’t remember – a spectre the notetaking breed spends an inordinate amount of time preparing for. But does that moment ever actually come? We’re in an age of “storage culture,” where you can save - or hoard - as much media to some nebulous ether space as you’re willing to pay £2.99 for. The decline of oral tradition and the excess of information at our fingertips has impaired our collective memory. We’ve been trained to believe there is virtue in preserving our lived experience the best we can, that it’ll be useful; that we’ll be better because of it.

Yet what we don’t remember in our messy realities is just as important as what we do. Joan elucidates the role of truth in her notebooks, “The point of my keeping a notebook has never been, nor is it now, to have an accurate factual record of what I have been doing or thinking.” She adds, “At no point have I ever been able successfully to keep a diary.” What happened doesn’t really matter: One might read my notes app and assume there was a time I was a paragon of wellness, but I didn’t. What mattered was how I felt – in that place, at that time. Joan reminds us, “Remember what it was to be [you]: that is always the point.” There is no better depiction of what it was to be me in 2012 than scrolling back through my iPhone notes app and reading how adamantly I believed that drinking apple cider vinegar in the morning would improve my confused, yet hopeful, existence.

“For so many of us, the Notes app, a simple and unassuming tool, contains the most honest portrait of our muddled but acutely felt reality, yet no amount of psychological tidying up will make it useful to anyone else but us.”

It’s all there in the Notes app. Twelve years of morsels and crumbs left over and swept aside as I consumed the world, an undertaking that left no time for real, committed diary-keeping, only my phone’s collection of scraps. Social media certainly did not tell a story of how it felt to be me, but rather how I wanted it to appear. The Notes app is the place where I remember who that girl is, how she felt, what she cared about. This is where Joan’s ideas feel familiar. This is the purest “écriture féminine.”

Some notes are functional –

A professor’s notes on a paper about Beowulf.

A shopping list: conditioner, razor heads, strapless bra, pitted cherries; followed by a manic orders DO LAUNDRY, STOP BITING NAILS, CALL MOM BACK

A grilled cheese recipe that includes a drizzle of maple syrup or a bit of apricot jam.

Some notes are aspirational –

A list of adjectives I want to use more frequently. Among them, “frothy.”

Talking points for when I’m fighting with my dad about politics.

A list of names for a cat I hope to adopt one day.

Things I wish I had said in the moment but wasn’t brave enough to say out loud.

Some notes are observational –

Everything the new guy I’m dating likes or mentions liking.

A loose transcription of a conversation I overheard on the bus – two people debating who was more disabled and deserved the seat.

A romantic idea: intimacy is two people laughing at the same time.

As I scroll through the scatterings it becomes clear their power lies in their ephemerality. Nothing in the Notes app is complete. No to-do list is ticked off. Some notes contain sentences I never finished, strings of words I couldn’t make sense of the next day, much less years later. It’s an ever-evolving medium unimpeded by the instinct to polish or refine. It can just be what it is at that instant in time. And yet, here we are, thumbs tapping away, attempting to codify our sense of self – who we wish we were, who we will never be – hoping one day it will all make sense. Joan suggests that through our notes, we “keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not.”

Staying in touch with our past selves is a tall order. She reminds us, “We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were.” For so many of us, the Notes app, a simple and unassuming tool, contains the most honest portrait of our muddled but acutely felt reality, yet no amount of psychological tidying up will make it useful to anyone else but us. In fact, if you read it, we’ll have to kill you.