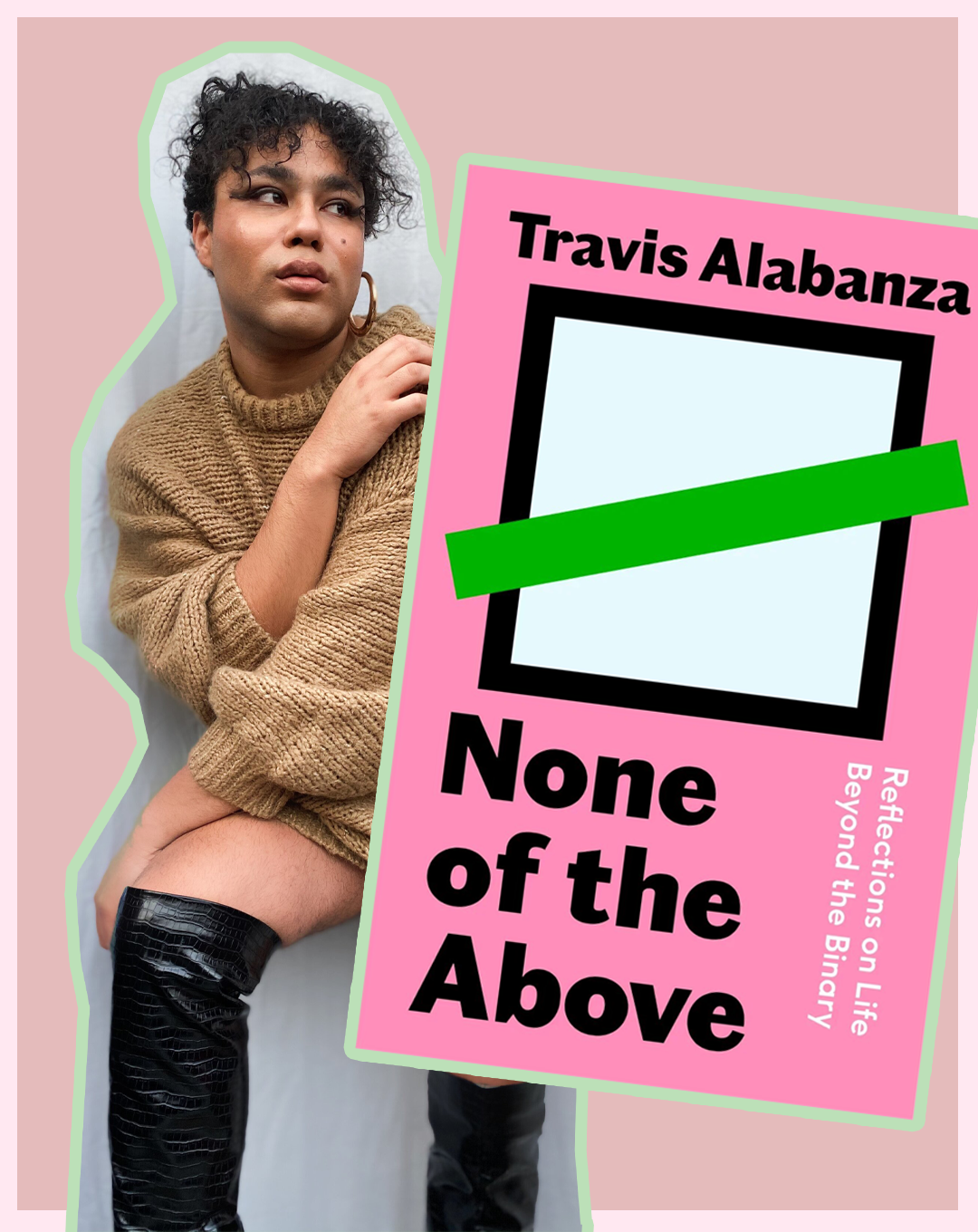

The (Bad) Taste Test: None of the Above Refuses An Easy Approach To Transness

While I was reading None of the Above, Travis Alabanza’s memoir of gender, art, politics, and their inevitable, messy intersections, I saw a lot of myself. I saw a lot of the ways in which I write, the page briefly becoming a mirror, as Alabanza stopped to acknowledge what kind of book None of the Above would be. Or, more importantly, what kind of book it wouldn’t be.

At the heart of None of the Above is an act of refusal that feels distinctly queer and, even more so, distinctly trans. In the prologue to the book, Alabanza writes that this is a book “without the end goal being understanding” something that, even now, feels like something radical - a continual challenge to both the need, and goal of representation. None of the Above, as its final chapter title implies, is for us baby, not for them.

What’s equal parts compelling and challenging about the book is looking at the ways in which Alabanza defines this “us.” It isn’t a nebulous one, that can easily be defined by using umbrella terms like queer or trans. Instead, by focusing on existing outside of boundaries, there’s an acknowledgement of the very specific kind of loss that comes with this, that being “neither” - because there’s a constant tension around how non-binary identities are treated, how trans they quote-unquote really are - means sacrificing both “state and community protection.”

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

When I was reading None of the Above, I saw parts of my own experience reflected back at me, as well as the ways in which I write. Earlier in August I had the (in)famous “how did you know?” conversation that Alabanza outlines in detail that’s at once lightly satirical, and excruciating for the way it captures the spotlight that can be cast on you in those moments. I was asked about the moment I know (which I couldn’t give a real answer to), and whether or not I’d ever thought about transitioning. The follow-up, on transitioning, rather than the nebulous curiosity around the act of knowing, goes to the heart of what seems like an uncertainty in non-binary identities. Or at least, an uncertainty in how they’re perceived; None of the Above, as much as it grapples with both clarity and the lack of it, is always focused on the fact that it’s the reactions of the world that so often amplifies these divisions, an unnecessary accumulation of binaries and boxes; ones that we’re forced to adhere to - whether this is something that happens to Alabanza themselves, as they constant grapple with the relationship between being one thing and perceived as another; or something as simple as (not) Steve, a straight man who goes to several of Alabanza’s shows, and finally finds himself with the - for want of better word - courage to finally paint his nails a shade of neon yellow.

For Alabanza, these things - the struggles of (re)defining the self - or small movements against the expectations of what it means to Be A Straight Man for someone like Steve are “all reactions to the same allergy - the gender binary.” Which is what leads to one of the most surprising, head-turning moments in the book: when Alabanza writes “I was not born this way.” Instead, they complicate transness itself - from its genesis to its lived experience thinking that rather than being born different they are “trans because the world made [them] so” and, at their most confrontational, write “I am trans because of you, not because of me.”

Like Alabanza, I’ve never been able to get a sense of where that why came from; if there are clear moments in the past that have lit the way to this moment in time, writing this sentence about my gender. Like Alabanza, “I am aware of the time we lose to gender,” although whether or not that time lost is in discovering transness, or trying to define it after the fact is something that I’m still unsure of. That the relationship between now and then might be about everyone else more than its about me. None of the Above offers more questions than answers; rightly cautious that the way that these questions are answered is done to placate a hypothetical cis reader - or cis person on the street, trying to understand but only if it means someone else doing the work - and Alabanza constantly sidesteps the expectations of what’s become seen as the mainstream, accepted face of trans narrative.

Even when they grapple with the fraught relationship between their upbringing and gender, they refuse to “give you the inspirational pathway to freedom.” That instead these moments of shaming are born from the shame of someone else; that, rightly or wrongly, transness exists in a kind of reactive state: at once brought about by the state of the world, but also silenced, mistreated, abused by it.

When I first sat down to write about None of the Above, I had a pretty clear sense of how I would approach it. With the title in mind, I knew I’d want to write about how the book avoids what we’ve come to define as trans writing: it doesn’t offer narrative of beats of coming out, of growing into confidence, of finding The Self. Instead, it explicitly says it won’t do this, stopping to point out that the chapters themselves aren’t interested in the kind of things that a certain kind of reader might have picked up the book to learn more about. And the more I grappled with these ideas, the more I found myself face to face with a fact that seems obvious, but sometimes difficult to grasp: the deep subjectivity of trans experience. That even a word like “trans” can mean so many different things, and that once you decide to use it, other people - as well as you - will have to grapple with what that word means.

As they navigate the tension between historical reality and the continued echoing of things we know to be untrue, Albanza argues that having non-binary become a legally recognised gender “brings with it an attempt to homogenise and control what could have been a beautifully uncontrollable option.” None of the Above is a riposte to these ideas of control; an embrace of the messy, the subjective, and the transformational. Showing that one of the reasons that the archetypal “Trans Narrative” so often struggles to fit onto the bodies and lives of trans people in the real world is that these narratives, changes, transformations, don’t always end and, more importantly, don’t have to.

Words: Sam Moore