On the Tyranny of Perfume Ads

Make it stand out

You know the woman in the perfume ad. She is gorgeous, thin. She’s turning heads on a night out; she’s in her power. She dances, laughs. She toys with the adonis. She emotes, but so beatifically it doesn’t leave a trace. Her script may change, but the message rarely does: there is a goddess in all of us. We can do what we want, when we want. It’s our moment to change the world. We’re free; we’re wild; we’re beautiful. Bold, tick. Modern, tick. Comfortable in our own skin - tick, tick, tick. These adverts are media artefacts heavy with the language of 21st-century popular feminism and the subtext is ultimately the same; that womanhood is an individual endeavour of transformation, aspiration and improvement.

Right now may be a golden age for tyrannical perfume advertising but these scented women have lived on our TV and cinema screens since the 1960s. This strange corner of media has always illustrated an element of that epoch’s prevailing fantasy about the essence of womanhood; in the 60s, the perfumed lady was fashionable, unapproachable, silent. In the 1970s, she was breezy, happy, everyone’s friend. By the 1980s, she was sexy but suburban, bold but unthreatening, a Cindy Crawford-type situated firmly in the domestic sphere, or else, in the case of one Estée Lauder ad, literally a bride. And in the 1990s, David Lynch’s hazy, dream-like adverts for scents by Yves Saint Laurent pushed the medium into the phantasmagorical realm, safely and deliberately removed from the grrrls of third-wave feminism and the raised eyebrow of post-modenity. Come the millennium, the fragrance dreamstate was taking shape, reflecting the low-lit, soft-glow, semi-ethereal femininity of the Y2K years. Guerlain deposited a naked woman in the desert to roam among barren trees, showering flower petals, and (imported) pampas grass, and Rochas plopped a model into a galactic rock pool wearing a slip dress. At the peak of the 00s celebrity perfume craze, Britney Spears and Avril Lavigne meandered, dazed, through mythical woodlands and twinkly skies, shilling some kind of aromatised star power.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Led by the 2012 Chanel No.5 commercial featuring Nicole Kidman (directed by Baz Lurhman), new perfume epics (some as long as 3 minutes) pushed the form into banally sinister territory. Chanel did it best; these lavish adverts aspire to cinema in story and style, and elevate the scented woman to an imitation of self-actualisation - she makes choices, she’s in charge. Kidman fled a life of fame to fall in love with a blessedly simple hunk, wretched with the decision to stay or go. More recently, Keira Knightley ran circles around hunk no.2, driving him mad with her impetuousness and motorbiking, and Marion Cotillard did interpretive dance on the moon with an adoring Frenchman. Burying the product in a romantic ‘story’, these ostentatious fairy tales achieved the pinnacle of one of the grimmest forms of modern advertising - they pretend they’re not selling us anything.

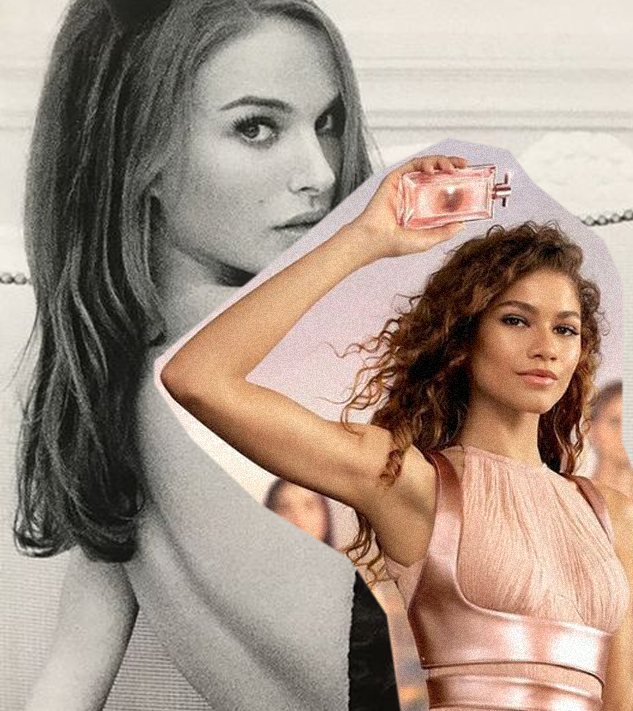

The specifics of these tropes are updated visually but never philosophically. Women in perfume ads are reliant on the central marketing strategy of the product - that this elixir will transform you, will liberate you, will make people love you. This year, Lancóme’s ad featured a bevy of all-ages celebrity faces - Julia Roberts, Zendaya, Isabella Rossellini, Hoyeun, Aya Nakamura (note: perfume ads generally treat diversity as a sleight of hand). Against a limitless white background, they smile and lip sync to a cover of What a Wonderful World. As the song kicks into an upbeat remix, they start power walking, dancing, showing the camera their best bad-bitch face. The brand described the campaign as a “rallying cry” for women. The tagline for the ad is “Make Life Beautiful”. As if smelling nice changes anything in the play by play of an average person’s day.

“Perfume ads are tasked exclusively with evoking feelings; they can’t show you the mechanics, they can’t (yet) pipe the scent through the screen. They must elicit sensation.”

A central trope in the perfume universe is a sparse landscape, primed for projection and malleable meaning. This non-world is barren but lovely - a desertscape, a lonely road, a wildflower meadow, a silent city. Any other inhabitants are essentially faceless. It’s boiled down to symbols only, reliant on a handful of signifiers (the tonal notes of the scent itself, or the product's faux-profound name). Flowers, stars, the ocean, the moon - all dance in service of the scented woman. In the latest Burberry Goddess ad, actress Emma Mackey (pared-down make-up, naked dress) runs through a savannah with CGI lions to illustrate her innate female divinity. For Yves Saint Laurent, pop star Dua Lipa stands on an empty beach yelling into the ocean about how free she is. These vast, majestic liminal worlds do not set these women free - they contain them. They’re snow-globes.

Perfume ads are tasked exclusively with evoking feelings; they can’t show you the mechanics, they can’t (yet) pipe the scent through the screen. They must elicit sensation, an imperative that’s lent them all a gentle anxiety. The ‘narrative’ is deliberately nonsensical; this is womanhood in vignettes and tableaux, buffed and polished and slightly stupid, often journeying but with empty purpose. The attempt at metaphor manages only either surreality (Zendaya defying gravity on a horse) or condescension (Katy Perry blessing an Italian village with her beauty). It’s lowest-common-denominator media, creating a type of flatness shared by all commodified feminism. The most manic recent example is a Miss Dior ad from 2022, featuring Natalie Portman in a sort of frenzy of performative female-ness. To prove her lust for life she: runs through a meadow; jumps into the ocean; yells in an open-top car; lets her hair dry naturally while lying on a rock; cries lusciously. The effect is sort of nothing - it’s too beautiful to relate to, too strange to incite joy, too desperate to convince you.

In our current era, as we wax and wane about who gets to arbitrate womanhood, the woman in these ads has become both the post-feminist ideal and an unreconstructed cipher. She’s consumed all her previous iterations, leaving her vibrating with the thrills of ‘having it all’, and an empty vessel for every viewer’s projections. Crucially, she doesn’t care. She is care-free. As a miracle of hegemonic postfeminism, she’s benefited from women’s liberation but is entirely untroubled by it. Her existence - the glamour, the opulence, and her place in the world as some kind of angel-meets-overlord - is designed to encourage us to wear our oppression more lightly, with less bother.

The insidiousness here derives from the lack of deviation from the mould; the ads read from the same play book, religiously. They look the same, sound the same. There’s been no real progression for this woman, not to mention no genuine humour, no laziness, no ugliness. It’s idealised; that’s advertising. But as a bastion of subjective consumerism, it is redolent of the messages that ripple under the current of everything else directed at women - that happiness, acceptance, liberation, are not destinations one actually reaches, but instead things to indefinitely yearn for. We can only seek to attain it, work hard to get it, with perfume ads to both remind us what we’re striving for and to reaffirm the fantasy at the heart of all this effort.

Words: Annie Corser