Frida Wannerberger’s ‘The Dinosaur Tree’ Explores Girlhood, Power, and Post-Feminism

Words: Rob Corsini | Art: Frida Wannerberger | Artist Portrait: Esther Bellepoque

Make it stand out

For Frida Wannerberger there is nothing like the experience of creating a painting. “There's something super magical about having an idea of something and then seeing it happen in front of your eyes,” she smiles. For years, painting provided the perfect outlet for her creativity - one that had just a single downside, the clothes she wore to paint. “I used to wear really ugly clothes, the ones that are too ugly to wear to the gym,” she laughs. For Wannerberger, the act of wearing ugly clothes didn’t sit right in her soul. As a child she loved dressing up and could never decide what to wear. “If there was a party at our house, I’d change outfits five times,” she remembers.

And so, having to wear ugly clothes while she painted was something that she complained about, regularly, to her friends. That was, until one of them gave her a piece of advice - that she could paint in whatever she wanted. From there she Wannerberger assembled a new wardrobe dedicated to painting - long white dresses and nightgowns, pearlescent gilets to keep warm. Even if it was too cold, she’d go all out with her makeup. “There was a point where I thought it was quite fun to provoke. I had two studios in Bank and I was just walking around with this paint-stained nightgown,” she comments wryly.

For Wannerberger, the act of dressing isn’t just about looking good - but about entering a persona. Wearing white dresses allows Frida the person to inhabit Frida the painter - and painting allows her to inhabit her subjects. “Taking on different personas through dressing up, I think you do that in a way when you paint as well, because you're almost acting out that girl. Well, I am, at least” she explains. Her solo exhibition, The Dinosaur Tree, is showing at London’s LBF Contemporary until February 5th.

While painting is Wannerberger’s primary medium, her route into the world of art came through fashion. Wannerberger knew that fashion’s narratives excited her more than the construction of garments. “If I compare myself to friends who could geek out on a seam, it’s just not that interesting to me,” she laughs. And so rather than making clothes, Wannerberger drew them - and enrolled in Fashion Illustration at Central Saint Martins.

“It's almost like these paintings of women become sort of a glorified sort of homage to a man. a little shrine to one man through a painting of this woman - encapsulating the experience that I had.”

While she was studying, Wannerberger primarily worked in two distinct mediums - line drawing and watercolour. “They’re quite different - but in a way they’re like very small versions of the paintings that I do now,” she considers. Since her time at CSM, Wannerberger has worked as an illustrator, studied an MA in Painting at the Royal Academy - but her practices have mostly been consistent, with just a switch to oil paint. “It needs a couple of days to sit and completely changes from what it looked like when you painted it,” Wannerberger explains. “The painting is painting itself, in a way.”

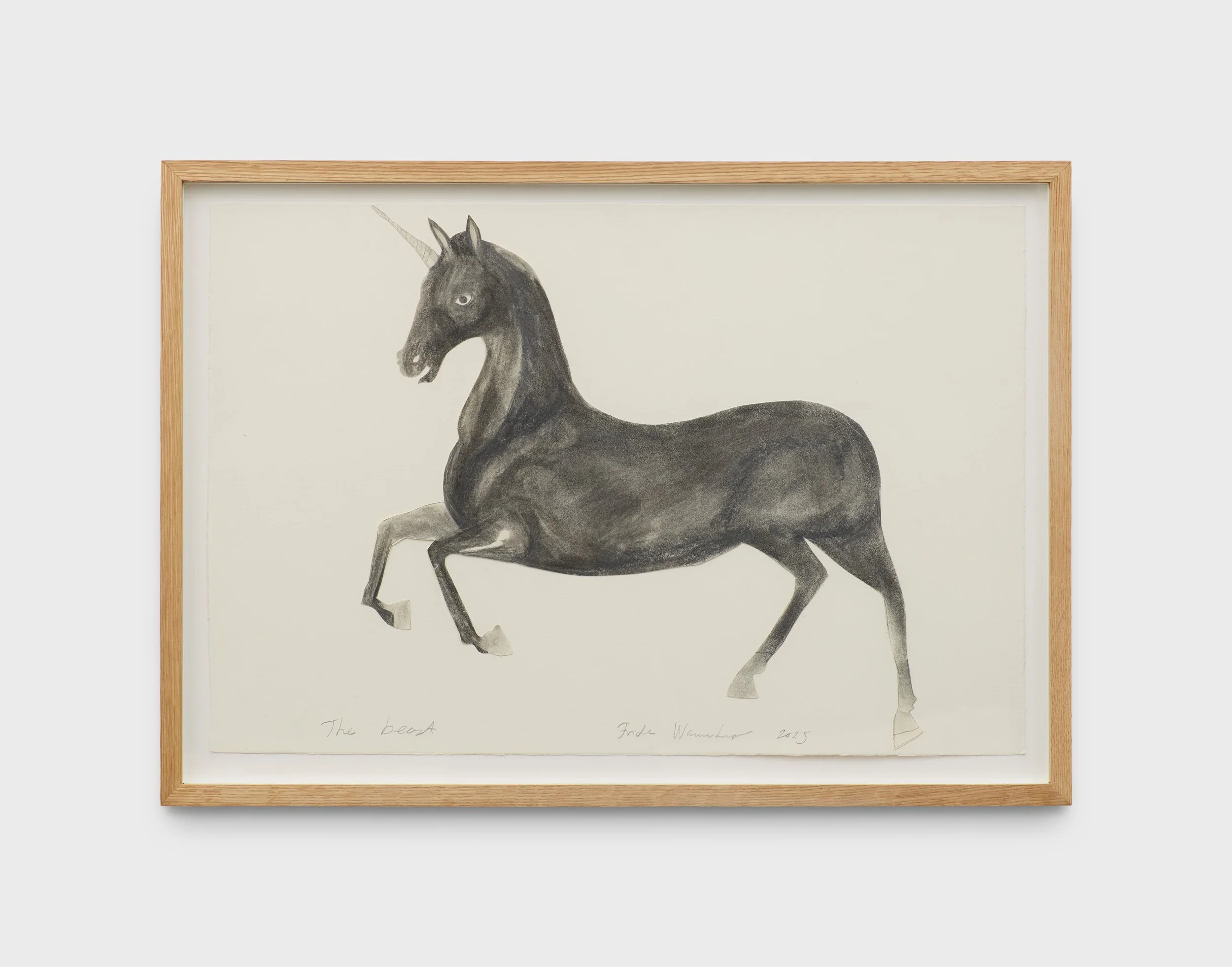

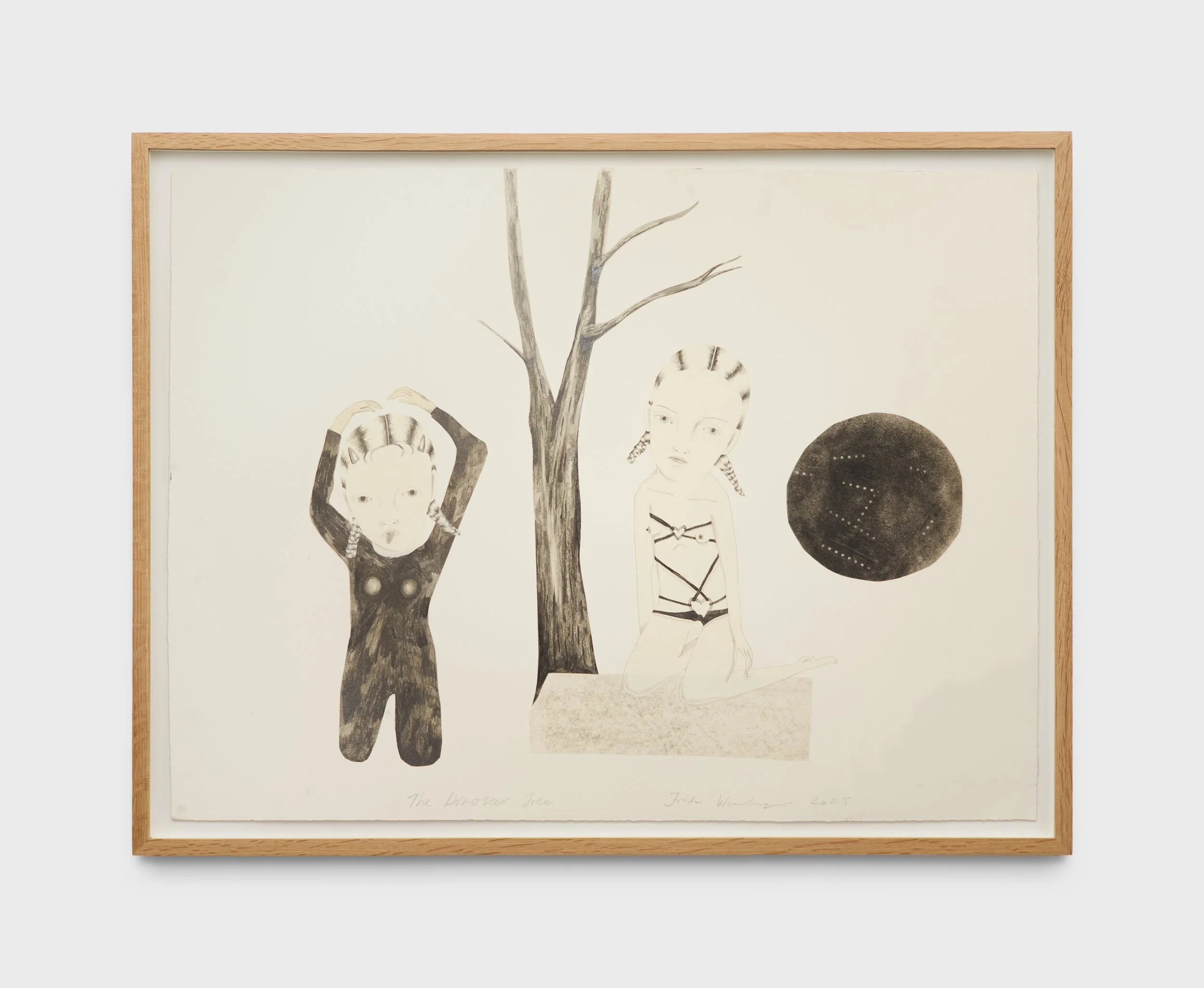

Wannerberger’s current exhibition, The Dinosaur Tree, features two distinct sections - the first is a group of oil paintings and the second is a series of pencil-drawn collages. All of the works feature girls - who are painted against black backgrounds and drawn in architectural cityscapes. There’s a flatness to the paintings which evokes the art of Tudor, Renaissance or even Late-Mediaval periods. “There's an innocence to the girls, but they’re quite sinister in a way,” Wannerberger describes, “The images probably seem innocent - a bit naïve or childlike on the surface - but if you look twice, you realise that they are not for children.”

Wannerberger painted the series after the ending of an intense relationship. She had always considered herself sure in self-conviction, but for the first time in her life she questioned herself. This self-doubt made her focus on the power dynamics that exist between men and women - particularly as they relate to sexual relationships. “It's almost like these paintings of women become sort of a glorified sort of homage to a man. a little shrine to one man through a painting of this woman - encapsulating the experience that I had,” Wannerberger explains. “It was important to immortalise that experience that I had. If it was taken away from me, at least I have it on paper. But I think it's very childlike behavior as well. Something about nostalgia, but also instead of playing with dolls, you play with paper to kind of feel like you're in control somehow.”

Yet Wannerberger’s focus wasn’t only on the relationship between men and women - but also between women and girls. Although Wannerberger’s paintings aren’t easy to definitively age, most of her subjects look like they straddle the line between womanhood and girlhood - and Wannerberger herself was thinking about this line. “I was starting to realise that you start to look at younger women in a different way,” Wannerberger says detachedly, “You start to almost sense that they could be a competition, whereas, that concept was super alien to me before. I never really considered myself as old until I did.”

One of the first indications that a darker truth exists within the sweetness of the paintings is in their names - with paintings titled ‘You Hurt Me So Much’, ‘We should dress you like a whore sometime’, or ‘Dirty Little Bitch’. Wannerberger’s titles are always literary - the exhibition also features a foreword by curator and art historian Salomé Jacques - and as Wannerberger was preparing for the exhibition she was taking written inspiration from Christine de Pisan and Sofia Coppola - but she was also reading Britney Spear’s memoir The Woman in Me. “It's a woman thinking about how she's being judged. Trying to be a good girl by appearing to not be a good girl. Wanting to please everyone, but also extremely sexualizing herself and being sexualized by the entire world,” Wannerberger considers.

Wannerberger has previously described her works as post-feminist - which allows her to imagine and depict subjects whose fundamental rights have already been met and who are able to live their own wants, needs, and desires - but this collection complicates that viewpoint. “The general state of the world has made me reflect a lot on what extent we can really change things. I think that's a very sad place to be in,” Wannerberger reflects. In considering her work outside of the post-feminist space - Wannerberger began to consider how femininity could be used to rebel against a capitalist, patriarchal system. “I felt like the way I could claim my space was to enhance my, I guess, womanhood,” Wannerberger maintains.

While the space of womanhood provides a way to challenge these forces, Wannerberger believes there is even more potential in girlhood. “If you take it back one notch and keep yourself within the girlhood space, it's not entirely appropriate for someone to start to sexualise you. It creates a space to kind of push the limits,” Wannerberger argues. It’s for this reason that she believes in the inherent power of girlhood as a vehicle for liberation, why girls remain the centre of her paintings, and why she believes that femininity should always be cognisant of its power. “You are a threat because you're the polar opposite. They can never be you.”

Frida Wannerberger’s solo presentation ‘The Dinosaur Tree’ is on view at LBF Contemporary January 9th 2026 through February 5th 2026.