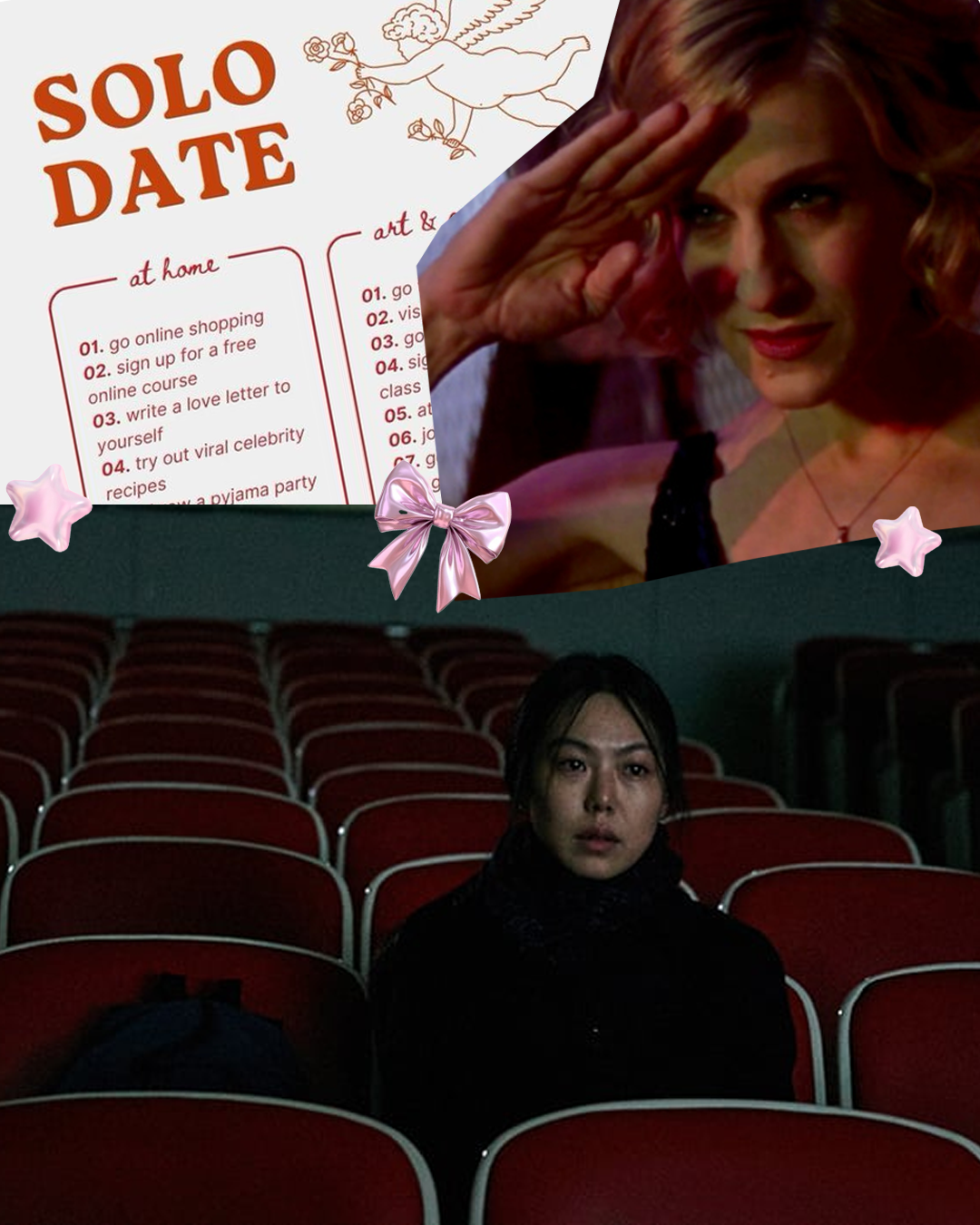

iPad Adults, Sabysachi, and Solo Dates: Why Do We Care About Going Out Alone?

Words: Janvi Sai

Make it stand out

It’s the evening rush hour on a weekday in midtown Manhattan. Legions of suits and Ann Taylor-wearers march out of their office buildings, tapping their ears twice. They look ahead and speak, but not to each other, let alone anyone physically around them. The wait for the light to change at a crosswalk brings a cacophony of conversations to a crescendo. They listen and talk to the voice in their AirPods. Tap tap. Silence. Next call. Hands are freed, momentarily - how much and how long do we want them to be?

Back at home, familiar television series with subtitles play against the companionship of an ambient YouTube video, and the contrasting loop of short-form social content stimulus. Netflix executives have sought to appeal to the era of casual viewing, reportedly encouraging their writers to create excessive exposition amidst a lack of active and attentive watching. There is rarely a pure TV-watching pastime anymore, when hands instinctively scroll into the social media abyss, like holding a drink or plate of room-temperature snacks as a crutch at a function.

This new public background music is increasingly visual and the norm, following us beyond the pharmacy and the waiting room. In a study published by the NIH, Music in Waiting Rooms: A Literature Review, researchers Lai and Amaladoss examined the efficacy of music in medical office waiting rooms intended to reduce patient anxiety. If the use of sound in these spaces is meant to calm the nerves that come with dreading medical appointments, its creeping spread into our downtime speaks to how contemporary anxieties have compounded daily life.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

A departure from the sterile and droning aesthetics of HGTV playing in a dental office with harsh overhead lighting, the audiovisual bombardment of today seems to have strayed from its more sanitised predecessors. But what bridges them all is the self-soothing effect they’re sought out to bring. Our media diet operates on an axis of overstimulation and numbness, a cycle where sensory excess and emotional void give way to one another.

The pull isn’t just chemical. Matching the addictive rush of dopamine is the drowsy relief of zoning out from our realities and ourselves. Like the draw of a lover holding your hand and leading you on a walk, our mass-media consumption offers comfort, and the passive relinquishing of thought. We knowingly, and willingly, fry our brains.

“Are solo dates romanticising a charmingly ordinary part of life, or are they othering unaccompanied outings, branding them as atypical? Does the trend destigmatise them, or contribute to stigma?”

Our cultural landscape is struggling with and appealing to alienation in every sense of the word, from feelings of powerlessness under hegemonic and institutional powers, to estrangement from others, and the self. Exacerbated by the simultaneous stage-and-audience of social media, this unease is evergreen. In the Sex and the City episode “Anchors Away,” Charlotte reacts in disbelief when Carrie gushes over her day out with herself, including movie-watching at The Paris Theater.

Charlotte responds in horror, “You went to the movies by yourself?” Carrie coolly defends, “Yeah. What, you’ve never done that?” Charlotte then shrieks, “No! I could never!”

The newly-single Charlotte proceeds to go view the same film at The Paris Theater but with her tough yet mothering gay friend Anthony in tow. Meanwhile, Carrie’s storyline and narration in the episode follow her time alone “dating” New York. Her chronicles in the episode could be interchanged with her infamous push-and-pull dynamic with romantic interest Big.

She seeks a table for herself in a diner, only to be dismissed with, “Singles at the counter,” and pitifully offered lithium-laced ice cream by an elderly fellow ‘single,’ like she’s being cautioned by the world against spinster status, and as if they’re a subhuman species. Carrie Bradshaw’s experience reflects a common occurrence with discriminatory roots deeper than the habitual. Women have historically been barred from dining alone. Feminists have long fought against it.

In 1868, journalist Jane Cunningham Croly was denied entry to a New York Press Club event at Delmonico’s, a steakhouse that, like many establishments in history, didn’t seat women unaccompanied by men. Croly returned with Sorosis, the professional women’s club she founded, to protest the ban. Their actions contributed to expanding public access for women, and Delmonico’s became one of the first restaurants open to unescorted women.

Over a century later, the saloon McSorley’s Old Ale House kept their motto: “Good Ale, Raw Onions, and No Ladies.” And when it was owned by a woman, she wasn’t permitted during operating hours either. That was until 1970, when lawyers Karen DeCrow and Faith Seidenberg of the National Organization for Women sued. Seidenberg v. McSorley’s Old Ale House found the bar’s exclusion of women violated civil rights laws. Around the same time, Betty Friedan and other NOW members staged sit-ins at men-only bars and restaurants, demanding equal access.

Today on TikTok, a top video tagged under #solodate has been viewed over 800,000 times. Users document their own “solo dates,” including sharing ideas for activities to do by ourselves outside the home, or filming themselves ordering and eating at restaurants alone. Though they are in the company of spectators, even if just expected ones.

Are solo dates romanticising a charmingly ordinary part of life, or are they othering unaccompanied outings, branding them as atypical? Does the trend destigmatise them, or contribute to stigma?

Indian luxury fashion house Sabyasachi has its own take. The designer label celebrated its 25th anniversary this year with ‘90s supermodel Christy Turlington walking the runway, a party attended by Anna Wintour, and an ink blue knit shift dress embroidered at its center with the large and colorful statement: “TABLE FOR ONE.”

Rather than positioning being with someone as the default, the phrase asserts itself without anticipating the need for justification, or compulsory companionship. The perennial social conditioning to doubt oneself without a chaperone is now reinforced by trad content, AI chatbots, and self-lobotimising media distraction.

As bell hooks wrote, “Knowing how to be solitary is central to the art of loving. When we can be alone, we can be with others without using them as a means of escape.”