The Dupatta Debacle: The Erasure of South Asian Influences in Fashion

Words: Nooresahar Ahmad

Make it stand out

The comments section of a TikTok is perhaps not the ideal place to discuss the nuances of cultural appropriation, but God loves a trier. On many a scroll recently, I have checked the comments on a post of a white girl fluttering in a garment that looks suspiciously familiar to my (British-)Pakistani eyes, and found debate unfurling like a saari. No, those trousers that are fitted until they reach the thigh then suddenly flow outwards are not ‘bloomers’, the commenters assert firmly: that is clearly a sharara. ‘Pleated pants’, they tut, is a ridiculous title to give what is clearly a shalwar. And don’t even get them started on that length of chiffon fabric snaking around the neck: not a ‘skinny scarf’ at all, but a dupatta.

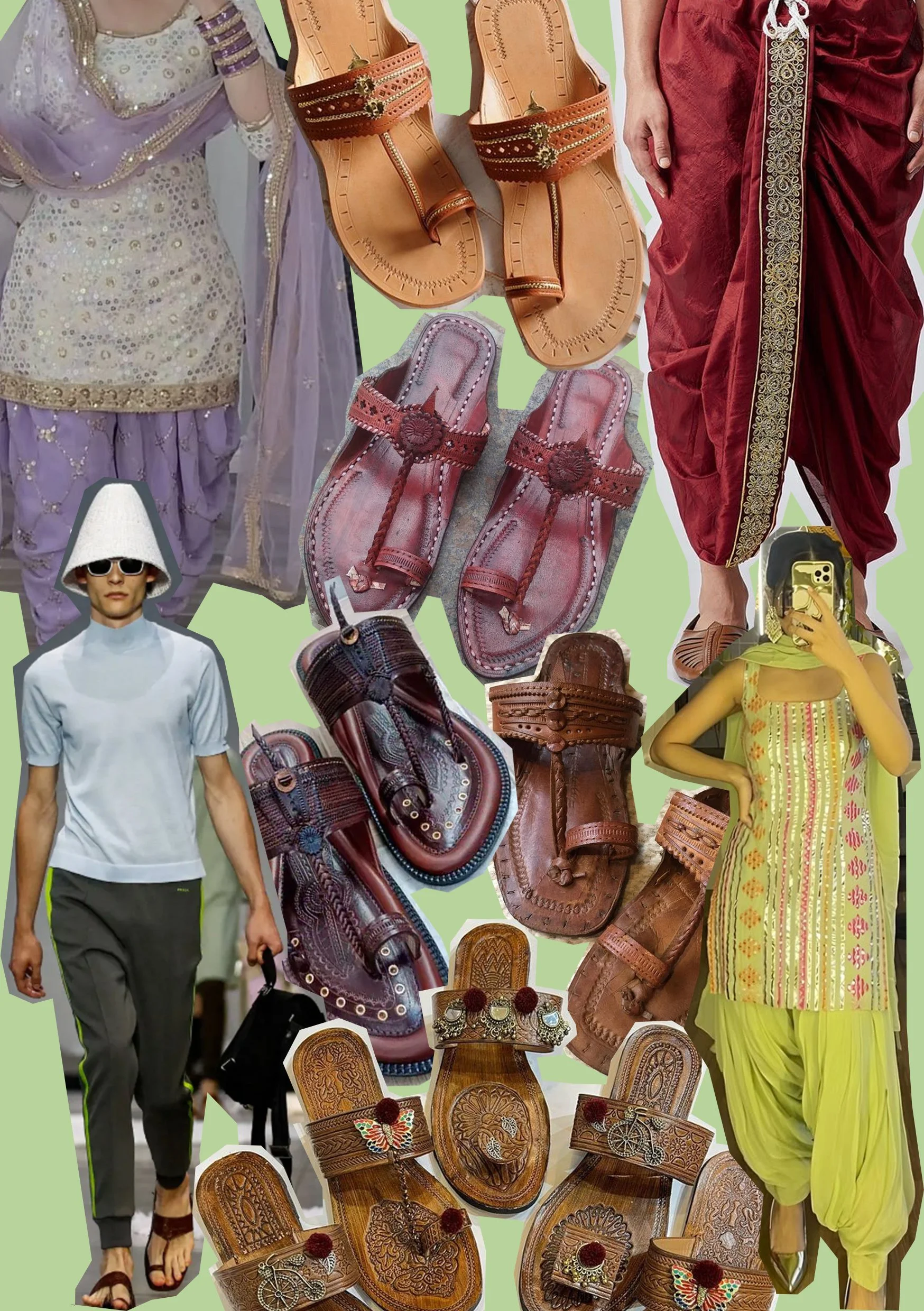

Well, they’re not wrong! It is a strange sensation to see someone posing in a garment (often with a distinct air of pride at the novelty of their fashion choices) that you usually see being worn by Aunties at the masjid, baddies at a shaadi, or your dad to bed. It’s not just on TikTok feeds that South Asian styles keep cropping up in unlikely places, either. In the past year we’ve seen draped trousers, reminiscent of the Indian dhoti, in Loewe’s S/S 2025 menswear collection, Gucci’s first bespoke saari debuted at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, and chappals on the Prada runway.

Of course, this is not the first time in history that European fashion has copied styles from South Asia. Richard Martin and Harold Koda note in their work Orientalism: Visions of the East in Western Dress that, since as early as the thirteenth century, “the East has provided recurrent resuscitation and expansion of Western dress…. Eastern ideas of textile, design, construction, and utility have been realised again and again as a positive contribution to the culture of the West.”

Amongst the spoils brought home from France and England’s colonial exploits, for example, were the patterned fabrics and sartorial possibilities offered by India, China and many African countries. By the nineteenth century, Indian fabrics were widely admired in Europe. George Birdwood, founder of the Victoria and Albert Museum in Bombay, wrote of Indian cottons in 1880: “Nothing could be more distinguished for the ballroom, nothing simpler for a cottage, than these clothes [...] with their exquisitely ornamented narrow borders in red, blue, or green silk.” Soon entire businesses and factories in Europe were dedicated to creating imitations of such subcontinental splendour.

By the 1910s, textile and fashion conservator Jaya Misra argues, the gradual abandonment of the corset and an interest in Neoclassicism meant that Indian accessories were creeping into the European fashion world again, from turbans to “harem” pants over tunics. The saari, worn in Europe as early as the late eighteenth century, had become a ubiquitous item of clothing in Parisian high-fashion circles by the 1930s. Inspired by Princess Karam of Kapurthala, Elsa Schiaperelli even designed her own line of saari-inspired evening dresses.

“There’s a reluctance, on the part of consumers and designers alike, to give credit to their South Asian origins.”

So what, if anything, is different this time, as Europe once again looks to India for its fashion inspiration? One interesting element is the reluctance, on the part of consumers and designers alike, to give credit to their South Asian origins. Influencer Devon Lee Carlson, in her collaboration with Reformation, for example, incited criticism by including a long skirt, crop top and chiffon scarf (undeniably reminiscent of the Indian lehenga and dupatta) in her collection and crediting its inspiration not to the subcontinent, but to British designer John Galliano. Gucci have raised eyebrows by describing their saari/lehenga as a ‘gown’. Last year, fashion rental company Bipty caused controversy by describing chiffon scarves not as a South Asian woman’s wardrobe staple but as a new ‘very European, very classy’ trend. But blatantly copying clothing and footwear while obscuring the origins is not an entirely new impulse, either. In the nineteenth century, for example, Kashmir shawls were renamed Paisley shawls after the area in Scotland where copies of the original were manufactured en masse.

The major difference this time seems to be the dulled-down approach to these South Asian-inspired pieces. In the past, Martin and Koda argue, when European designers leant heavily from the subcontinent, they did so “for the purposes of rendering Western dress richer and more exotic”. These ‘exotic’ elements included the elaborately embroidered and boldly printed fabrics which, both in colour and complexity, often went far beyond the limits of what would otherwise be acceptable in European fashion.

It seems, though, that the “exotic” is no longer a selling point. Instead, it’s popular to borrow the general shape of the garment while significantly muting the look, until it is something that can fit the descriptor of being ‘very European, very classy’. The vividly printed dupatta becomes a plain, ‘Scandinavian’ scarf, and an adorned lengha is converted into a bland chiffon skirt. Artist and archivist Sanam Sindhi has noted this strange turn, writing of Tom Ford’s Spring 1999 mirror work tops that were obviously inspired by Indian cholis from Kachchh: “While the credit was nonexistent, at least the designs were something to take notice of. Now it seems fashion houses can’t stop making a spectacle of their odes to the subcontinent and yet I’m not seeing garments that justify the references.” The clothes that have recently caused controversy for their uncredited lending from South Asian textiles and fashion are recognisable in silhouette, yes, but the fabrics are curiously unpatterned and monotone.

This is no doubt due to a general cultural shift towards conservatism in fashion, as seen in the rise in the last few years of the ‘Quiet Luxury’ mode of dressing – a style that does little to hide its contempt for working class, black and brown styles that favour a bolder look, and calls back to a European heritage that is fixated on not just quality and understatement, but whiteness and wealth. Plus, the rise in racism directed towards South Asians online, and a general and growing hostility towards perceived foreignness in Europe mean that the so-called ‘exotic’ origins of a garment have to be obscured in order to market them in a way that aligns with current consumers' sensibilities.

These consumers may not want to be dressed like an Indian, but they are more than satisfied in their banal, floating fabrics that, bled dry of their origins, are turned into something sufficiently chic and suitably European.