AI and Workplace Hellscapes: The Contemporary Gothic We Deserve

Words: Mya Ward

Make it stand out

For the past three years, maybe longer, I’ve had to start attending to the impossible habit of confirming, by my own uncertain authority, what is real and what is false. The mascot of the new dumpling spot up the street, an aproned red panda listed forward with a Cheshire grin, a saucer of amorphous, tan globs in his left paw. Lurid Los Angeles-style billboards and drop-down banners advertising hyaluronic acid and injury attorneys and smiling Scientologists. I inspect their hands and arms and gaping teeth, scouring for the sixth finger, the spare limb, the sinistral silhouette of an extra tooth. As thorough as I am, I concede that I miss a lot. I always do. AI renderings have gotten to be nearly imperceptible and if current trends hold, it won’t be long before they will be indistinguishable from reality.

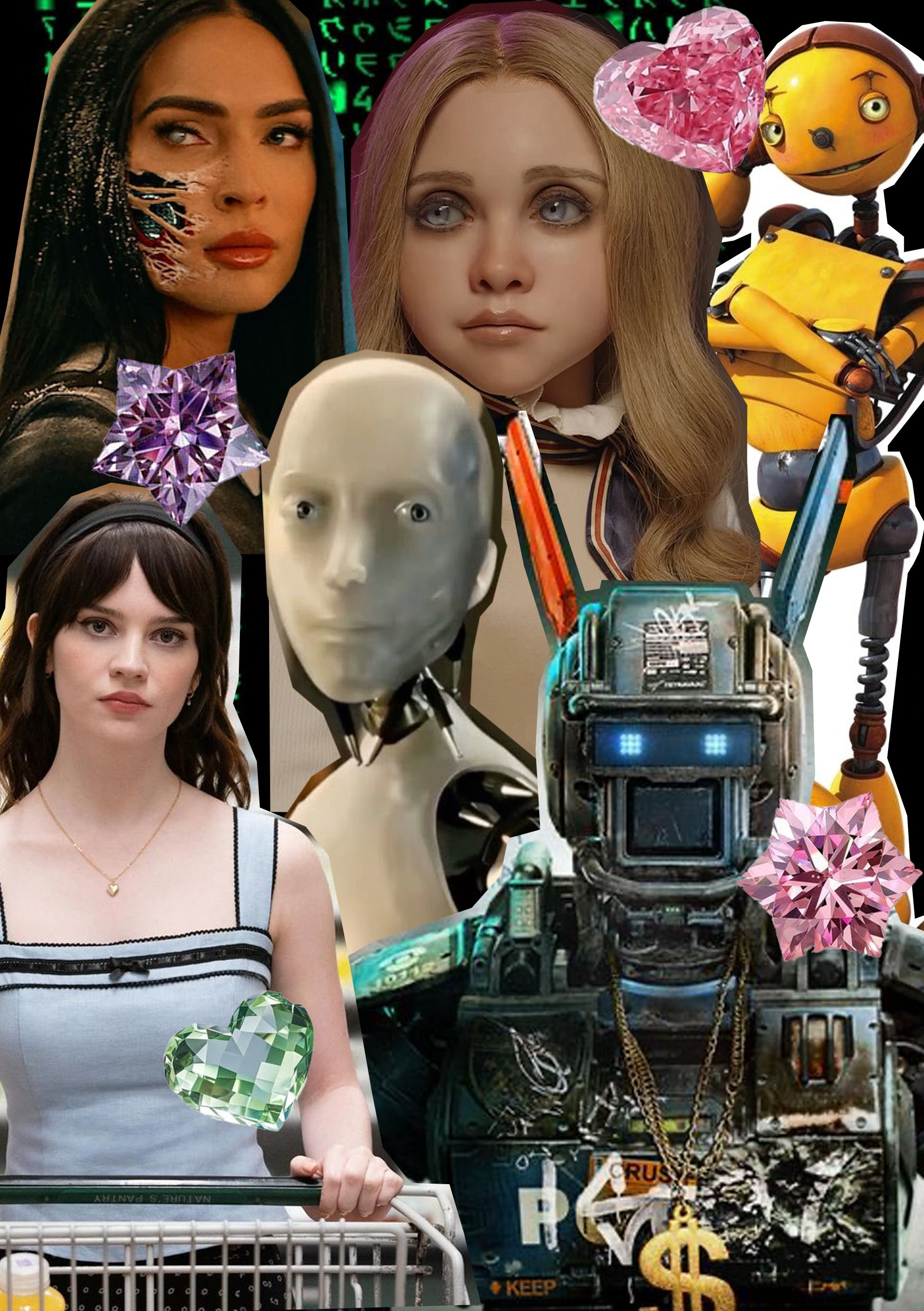

The media landscape has been swept by works dramatising, satirising, and overall aestheticising the widespread distaste and dread of AI, of large corporations, and of interpersonal and internal illegitimacy. Apple TV’s Severance (2022-) follows the dazed employees of a biotechnology corporation who underwent a procedure that separated their work life from their personal life, retaining no recollection of one while living out the other. Ripe (2023) by Sarah Rose Etter follows Cassie, a year into her job at a Silicon Valley start-up, she cascades down a black hole of long hours, unethical practices, drug-fuelled benders, depressive episodes, and late stage capitalism-fuelled acrimony. Works like Severance and Ripe do not just embody the solemnity of the gothic genre as it exists in 2025, but imprint it with a certain edge of uncanniness. It may not be the gothic we’re most acquainted with, but it is the gothic we deserve.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

In the late 19th century, with World War I premonitions and apprehension around scientific advancement steeping the cultural dialogue, a gothic of foreign monsters, pathogens, and Promethean science emerged. Two of the most favoured and enduring novels of the time, Frankenstein (1818) and Dracula (1897), envisioned two monsters from the same bucket of fears. Frankenstein’s monster, a personified fatal flaw, represents man’s rejection of humanity in pursuit of innovation. Dracula delivered all of the Western anxieties regarding the Eastern “other.” In the novel, there is a scene where Jonathan Harker, teeming with lust for Dracula’s undead brides, recoils after learning that they feast on a defenseless infant. He defies their humanity declaring, “They are devils of the Pit!” Jonathan’s reaction does not make the brides less beautiful, or even less enticing, but it does make them less human.

Regardless of its mode, the gothic teaches that the monster will always resemble us. The gothic teaches that the monster will always deceive us. Most of all, the gothic enforces upon us the responsibility in filtering humanity from its imitations. The living from the undead.

“Regardless of its mode, the gothic teaches that the monster will always resemble us. The gothic teaches that the monster will always deceive us.”

This particular gothic impulse around authenticity and artifice rhymes with the current state of pop culture. Corporations, desperate to transform every viral trend into terminal profit, have begun attaching themselves to Gen-Z’s ache for community and identity. The rise of pop ups such as the Miu Miu Book Club and the Dior Café signify that the market has shifted from selling us tangible products with ideas attached, to repackaging our own ideas and desire for connection, and selling them back to us at a price.

That corporations are increasingly beginning to utilise AI that synthesises humanity’s words, works, ideas, and identities into a generative sludge is as inoffensive as it is accessible. The muck is good enough to escape the absent doom-scroller, the passerby, the worn teacher, but it’s not good enough to truly trick us right? We like to believe that – when attentive – we would notice that there is something off about the logo, something shiny and unpleasant about the billboard model, something too adept and treacly in the essay. But the unhappy truth is that this judgement is getting harder. Our discernment is getting weaker.

In his essay on the “The Uncanny,” Sigmund Freud grappled for a definition of the word. Of the feeling that is so simple to diagnose, yet not so simple to index. Freud enumerated triggers for the uncanny, ranging from dopplegängers to automatons, with the major theme being that in the presence of these triggers, our humanity – our individuality – is called into question. We righteously interpret AI as an affront to the human instinct to distinguish what is human and what is not. Because if an algorithm can be a better artist or a better writer or a better friend than most of the population, then what use are we?

“We righteously interpret AI as an affront to the human instinct to distinguish what is human and what is not. Because if an algorithm can be a better artist or a better writer or a better friend than most of the population, then what use are we?”

It is here, at the juncture of rationale and paranoia, where the gothic is borne. Though many classic gothic works are respected today, at the time of its peak, gothic literature was something akin to pulp fiction. Cheap, prosaic, reasonably entertaining, thought of as lacking in substance or significance, tilling with sentiment. As with today’s media, there were a few diamonds in the rough – gothic novels that surfaced from the mediocrity of its predecessors – but those were few and far between. Gothic literature was simply a facet of popular culture, valuable not for its merit, but for its profitability.

With the new gothic, there will be shows like Severance that contrive sublime landscapes of sterile corporate hallways, echoing and infernal and blinding. There will be books like Ripe that can translate the subtle euthanasia of corporate life. Yet there will also be films like Mountainhead (2025), with self-assured cynicism and derivative multimillionaire and billionaire “tech bros” character sketches. Though entertaining at times, this film ultimately failed because its narrative relies too heavily on conveying the real-life conceit and contemptibility of tech bros, rather than telling a fictional story. Nevertheless, Mountainhead still fits neatly into the new gothic, by the ethic of distorting that which we are afraid of.

It is practically archaeological, the way that the gothic preserves our fears and evinces our truths. Our fears are our DNA, marked in the proteins. The gothic is the ceremony, distinct only in circumstance and occasion – and the contemporary circumstances find us holding up a mirror to the uncanny of our real lives, and finding there what scares us most.